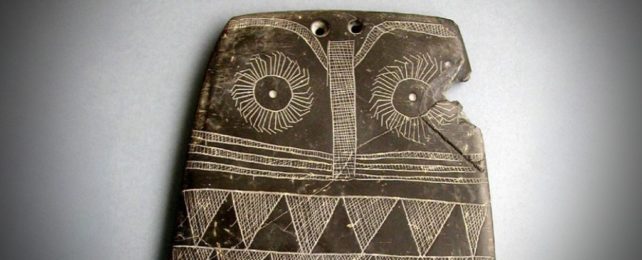

Thousands of ancient owl-shaped slate plaques found in tombs and pits across the Iberian Peninsula were thought to represent deities or hold ritualistic significance to the Copper Age societies that crafted them.

But new research suggests the palm-sized plaques decorated in geometric patterns and with two engraved circles at the top might be the work of children.

Numbering in the thousands and made from slate, the owl-like objects – previously dated the stone objects to be between 5,500 and 4,750 years old – may be "the archaeological trace of playful and learning activities carried out by youngsters," according to the team of Spanish researchers behind the new study.

"Owl-like objects made in stone provide perhaps one of the few glimpses to childhood behavior in the archaeological record of ancient European societies," they write.

Led by Juan Negro, an evolutionary biologist at the Spanish National Research Council's Doñana Biological Station in Seville, the team of researchers compared the slates to the facial features of local owl species found in Spain and Portugal and made replicas to see how easy they would be to engrave.

They suggest kids would have been able to easily engrave slate using pointed tools made of flint, quartz, or copper, creating 'body' patterns that emulate the streaked plumage of owls, and the circles for eyes are unmistakably owl-like, casting an unwavering stare straight at the observer.

The "owliness" of the designs is comparable to the drawing skills of modern school children who depict owls in much the same way.

Two small holes at the top of many plaques also showed no signs of wear. This, the researchers say, means that the stones were probably not strung up as plaques, as other archeologists have claimed. Instead, Negro and colleagues suggest owl feathers could have been placed in the holes to resemble the tufts of feathered friends.

Archeologists have debated the meaning of these objects for more than a century, and this research simply reinvigorates that conversation.

Negro and colleagues don't rule out the possibility that the plaques could have been later used in rituals as burial offerings; they say young people might have paid homage to their elders by leaving objects they had made together as tributes to the deceased.

Regardless of how the plaques were made or what they were used for, their uncanny resemblance to two owl species common in Spain and Portugal – the little owl (Athene noctua) and the long-eared owl (Asio otus) – can be seen in the image below.

"When the stone is carved, it has the peculiarity of alternating its natural black color with the white of the lines that have been engraved, a characteristic that facilitates the imitation of the cryptic plumage of the owls," Negro and colleagues write.

"These slate slabs, so characteristic of the Copper Age in Iberia, could have been part of the learning process to handle stone objects," adds art historian and study author Víctor Díaz Núñez de Arenas of Complutense University in Madrid.

Not all archeologists are convinced, however. They say the evidence presented isn't particularly strong or scientific and that the slates are unlikely the playful creations of children because they appear to be so widely made in a standard way.

"If children, as the largest demographic of these communities, were making them, these kinds of plaques should be much more common, when in fact, those plaques with owl-like qualities make up only about 4 percent of all plaques," Katina Lillios, an anthropological archaeologist at the University of Iowa, told New Scientist.

What no one is questioning is the way owls have long been entwined in human culture. These majestic birds have been depicted "since the dawn of art" in the Paleolithic period, Negro and colleagues write, on coins and ceramics, in mosaics and cave art, from Spain and France to Australia and Africa.

"That may have to do with frequent encounters with actual owls, creatures of the night with salient anthropomorphic features."

The study was published in Scientific Reports.