Tiny balls of mineral are opening a new window into the history of life on Earth.

These millimeter-sized objects are more than half a billion years old – the fossilized embryos of animals that lived during the early Cambrian period, some 535 million years ago.

They belong to a group called Ecdysozoa, which includes insects, spiders, crustaceans, and worms.

The adult forms of the embryos can't be positively identified, though a team of paleontologists led by Mingjin Liu of Chang'an University in China believes they may be closely related to Saccorhytus, a genus represented by a single species – a tiny, peculiar Cambrian-era creature with no butthole.

The fossil record has a lot of things like crabs and insects – creatures with hard shells that cope well with the fossilization process. Ecdysozoan embryos are much rarer, because they are considerably more delicate. When we do find them, they are highly prized, because they can offer insight into the early development of long-extinct animals.

The seven embryo fossils discovered by Liu and colleagues were found several decades ago in the Kuanchuanpu Formation in China, a fossil bed rich in microscopic fossils.

In fact, the Kuanchuanpu Formation has yielded an abundance of fossilized embryos, but those belonged to the Cnidaria phylum, a group that contains jellyfish, anemones, and corals.

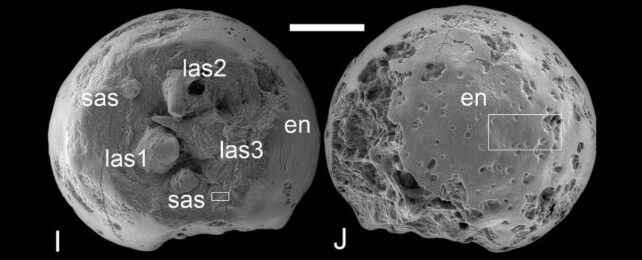

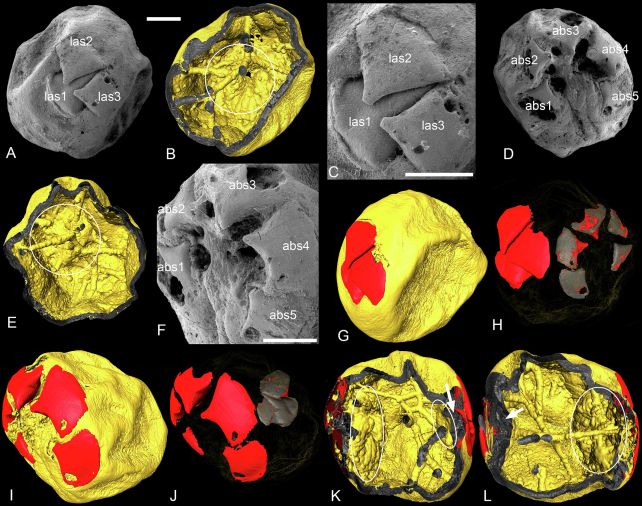

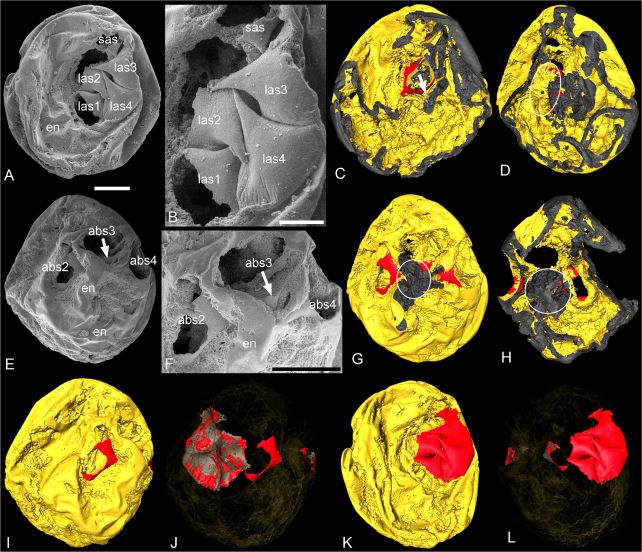

The new find is the first in the assemblage to represent Ecdtsoza. The once-soft tissues making up each embryo have long been replaced by calcium-phosphate minerals as they decayed in the sediment at the bottom of a marine environment. This fossilization process preserved the three-dimensional anatomy of the embryos in stunning detail.

Based on the number and arrangement of the plates forming the embryos' exoskeletons, called sclerites, the researchers classified the tiny organisms as two new taxa: Saccus xixiangensis and Saccus necopinus.

Because we don't know how these two organisms would have continued to develop, a lot of mystery remains. But their anatomy is wonderfully clear.

The embryos, each enclosed within a smooth envelope, have bag-like bodies, with no evidence of any limbs. The plates on their exoskeletons are arranged radially at their heads, and bilaterally at their tails, suggesting their bodies have a mirrored left and right side much like our own. Meanwhile, an absence of hair-like appendages called cilia places them in the Ecdysozoa.

Interestingly, there are no orifices in any of the embryos. This means that they are probably at a stage of their embryonic development before the formation of a mouth or anus. But the lack of deformation in the exoskeleton suggests the formation of the cuticle, which would mean that the embryos were close to hatching at the moment of their demise.

The large size (for an embryo) and hollowed-out middle of each fossil is indicative that each of these embryos once fed upon a large yolk, relying thereon for sustenance until they were able to grow mouths and start fending for themselves.

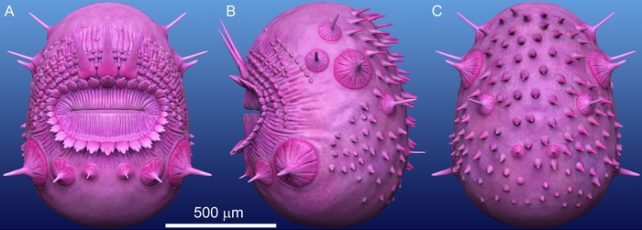

Faced with the mystery of how the embryos may develop, the researchers turned to adult fossils of an organism with similar characteristics that lived 540 million years ago, potentially providing a clue.

Saccorhytus coronarius was found in the same Kuanchuanpu Formation as Saccus. It also had no limbs, no cilia, a bag-like body, a giant mouth with radial structures around it, bilateral symmetry, and no anus. And it measured around a millimeter across.

It's possible that Saccus could have grown into something similar, closely related to Saccorhytus coronarius, especially since their body cones resemble those of the latter. If so, Saccus and Saccorhytus might both be basal Ecdysozoans, suggesting that the earliest ancestors of the group had a bag-like body, and the worm-like form emerged later.

Isn't it amazing what you can learn from seven tiny balls of calcium phosphate.

The research has been published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.