Scientists have bridged a missing link in the reptile tree of life.

That link is the tiny skull of a lizard-like creature "profusely ornamented" with features that suggest it gave rise to all living lizards, snakes, and the sole survivor of another reptile group found only in New Zealand.

Named Taytalura alcoberi, the fossilized skull is pegged as the most primitive scaled reptile discovered to date, the first fossil of its kind unearthed in South America, and the most complete early lepidosaur fossil ever found, according to the international team behind the discovery.

Lepidosaurs are scaled reptiles such as lizards, snakes, and New Zealand's tuatara, which together represent the most diverse group of land-living vertebrates alive today. Yet little is known about their early origins compared to the other arms of reptilian evolution which produced crocodiles, birds, and turtles.

"The almost perfectly preserved Taytalura skull shows us details of how a very successful group of animals, including more than 10,000 species of snakes, lizards, and tuatara, originated," says paleontologist and museum curator Ricardo N. Martínez, at the National University of San Juan in Argentina.

The discovery of the inch-long skull also has scientists reconsidering what they knew about reptiles in the Mesozoic Era, which is often known for its enormous reptiles and towering trees, and rethinking where the search for ancient reptilian fossils should go next.

"There was a universe of fauna sneaking among bigger, clawed or hoofy paws," says paleontologist and co-author Sebastián Apesteguía at the Universidad Maimónides in Buenos Aires.

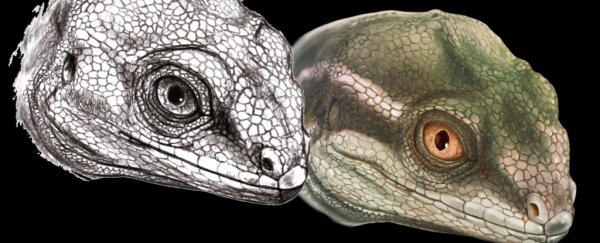

An illustration of Taytalura. (Jorge Blanco, 2021).

An illustration of Taytalura. (Jorge Blanco, 2021).

"Taytalura teaches us that we were missing important information by looking not only for bigger animals, but for also thinking that the origin of lizards occurred only in the Northern Hemisphere as evidence seemed to support until now."

The fossil, found in Ischigualasto Provincial Park in northwest Argentina, is about 11 million years younger than the oldest known lepidosaurs from Europe, but one of the best-preserved specimens of its kind, which means the team can have more confidence in their analyses.

"It looked more primitive than a true lizard and that is something quite special," says Tiago R. Simões of his first impressions of the skull, which measures 32 mm (1.25 inches) long.

The fossilized Taytalura skull. (Ricardo Martinezl).

The fossilized Taytalura skull. (Ricardo Martinezl).

It's a lucky find, especially considering the origins of lepidosaurs have been a gaping hole in evolutionary knowledge because of an "extremely patchy early fossil record comprising only a handful of fragmentary fossils", mostly found in Europe and often poorly preserved, the research team explains.

"All other known fossils are too incomplete, which makes it difficult to classify them for sure, but the complete and articulated nature of Taytalura makes its relationships much more certain," says team member and paleontologist Gabriela Sobral, from the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart in Germany.

In a cross-continental effort, the research team examined the skull's structure using a high-resolution micro-CT scanner and analyzed the images. The Taytalura skull had unique teeth and an unusual combination of features the team was not expecting to find in such an early specimen, preserved in three dimensions of astonishing detail.

"The extraordinary quality of preservation of the fossils at this site [in Argentina] allowed something as fragile and tiny as this specimen to be preserved for 231 million years," says Martínez.

Tayta means father in Quechua, the language of the Quechua people of the South American Andes, and lura is the Kakán word for lizard, spoken by Diaguita people of northwestern Argentina, where the skull was found.

Life restoration of the Taytalura skull. (Jorge Blanco, Gabriela Sobral and Ricardo Martínez).

Life restoration of the Taytalura skull. (Jorge Blanco, Gabriela Sobral and Ricardo Martínez).

Some of its features resembled modern tuatara more than living lizards and snakes, which suggests the latter actually represents a major deviation in evolution – not so much the tuatara living on windswept New Zealand islands.

Martínez and the team also deployed statistical tools to test the likelihood of possible evolutionary relationships for Taytalura, and to estimate the timing of various evolutionary departures that branched into other forms of life.

These analyses, based on a comprehensive dataset of reptilian fossils, helped Taytalura find its place in the evolutionary tree, nestled in between true lizards and tuatara, and all other reptiles.

What's more, the discovery of Taytalura in Argentina suggests that early lepidosaurs were probably able to migrate much further than previously thought – across thousands of miles on the ancient supercontinent Pangea that later split into the continents we see today: Europe to the north and South America in the opposite hemisphere.

Quite the journey for this teeny reptile.

The research was published in Nature.