Over 70 million years ago, dinosaurs lumbered through a wintry landscape in what is now Alaska. At the time, the Prince Creek Formation (PCF) was above the Arctic Circle and would've had constant darkness for four straight months.

The below-freezing temperatures and occasional snowfall were inhospitable to many, but it seemed to suit a tiny rodent-like creature, similar to an Arctic shrew.

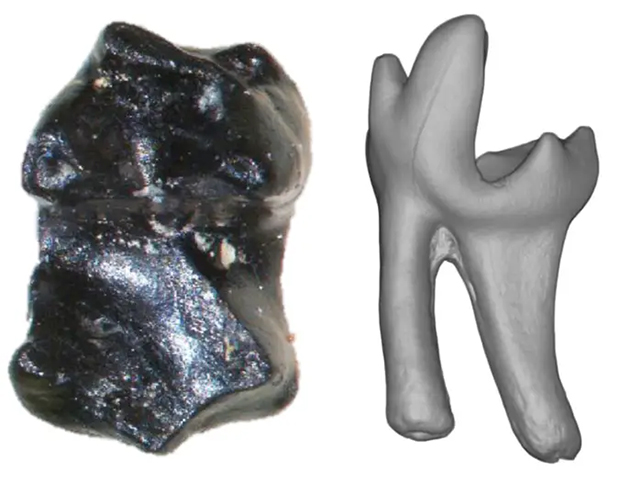

A few inches long and weighing about 11 grams – the equivalent of two nickels – the Sikuomys mikros, which roughly translates to "ice mouse," was a miniature mammal that lived in the frigid climate along with all sorts of dinosaurs.

The PCF is rich with dinosaur fossils. Scientists have found 13 species, including T.rex and Triceratops relatives.

Jaelyn Eberle, a professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder, studies the warm-blooded animals that scurried among them.

She and her colleagues described the S. mikros based on its teeth in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology in August. Each tooth is only about 1 to 1.5 millimeters.

"It is kind of interesting to imagine all these great big dinosaurs marching around" alongside the shrew-like animal, Eberle told Insider.

"These are smaller than your average house mouse, so these are itty-bitty guys."

Finding teeth the size of mustard seeds

When paleontologists find a dinosaur at the PCF, they also bag up some of the sediment around the fossils. They wash away the tiny dirt particles and keep larger objects from escaping with super-fine mesh.

Finally, they search the remaining debris under a microscope.

"There's no way we would spot a millimeter size tooth in the field," Eberle said. But with this technique, they found over a dozen teeth from three separate sites.

While sifting through the sediment turns up other mammal bones, it's difficult to tell what animals they belong to if they're not part of a larger skeleton, Eberle said.

"Teeth are going to be, for mammals, your most diagnostic fossil to find," she said. The S. mikros' teeth were significantly different from its near relatives to seem like a new species.

They then figured out the animal's size based on its tiny chompers.

A small size helps when food is scarce

The lack of a skull and other bones makes it difficult to determine a lot about the S. mikros. But based on how some related species live may give clues, Eberle said.

Comparing S. mikros with modern shrews and voles, Eberle said the ancient animal may not have hibernated.

"They were probably overwintering by staying awake and munching, probably feeding year round, maybe hiding under leaf litter or underground, which a lot of mammals do, and feeding on whatever they can sink their teeth into," Eberle said. That includes insects and other invertebrates, like worms.

The paper notes that with modern mammals, animals with larger body masses tend to live at higher latitudes in colder climates. Typically, they can store fat to help them survive colder months when there's little food.

S. mikros doesn't seem to fit that trend. It has some relatives that lived further south, "and they're about three to five times bigger than this little guy that lived in Alaska," Eberle said.

That suggests its tiny body is an evolutionary adaptation.

"Small size is probably selected for because the smaller you are, the less food you're going to need to keep you going in the winter," Eberle said.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: