Scientists have been able to direct a swarm of microscopic swimming robots to clear out pneumonia microbes in the lungs of mice, raising hopes that a similar treatment could be developed to treat deadly bacterial pneumonia in humans.

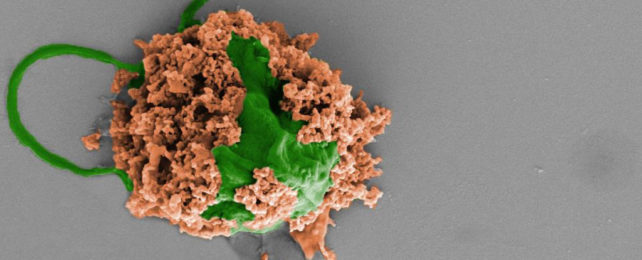

The microbots are made from algae cells and covered with a layer of antibiotic nanoparticles. The algae provide movement through the lungs, which is key to the treatment being targeted and effective.

In experiments, the infections in the mice treated with the algae bots all cleared up, whereas the mice that weren't treated all died within three days.

The technology is still at a proof-of-concept stage, but the early signs are very promising.

"Based on this mouse data, we see that the microrobots could potentially improve antibiotic penetration to kill bacterial pathogens and save more patients' lives," says Victor Nizet, a physician and professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

The nanoparticles on the algae cells are made of tiny polymer spheres coated with the membranes of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell. These membranes neutralize inflammatory molecules produced by bacteria and the body's own immune system, and both the nanoparticles and the algae degrade naturally.

Harmful inflammation is reduced, improving the fight against infection, and the swimming microbots are able to deliver their treatment right where it's needed – it's the precision that makes this approach work so well.

The researchers also established that the microbot treatment was more effective than an intravenous injection of antibiotics – in fact, the injection dose had to be 3,000 times higher than the one loaded on to the algae cells to achieve the same effect in the mice.

"These results show how targeted drug delivery combined with active movement from the microalgae improves therapeutic efficacy," says Joseph Wang, nanoengineer from UC San Diego.

In humans, the pneumonia caused byPseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria used in this study occurs after patients are put on a mechanical ventilator in intensive care. The infection often prolongs stays in hospital and significantly increases the risk of death.

The researchers are confident that their new method can be scaled up as required, and would be straightforward to administer to the lungs of ventilated patients (the microbots were delivered to the mice through a tube in the windpipe).

Next up for the team is more research into how the microbots interact with the immune system, then scaling up the work and getting it ready to be tested in larger animals – and then eventually, humans.

"Our goal is to do targeted drug delivery into more challenging parts of the body, like the lungs," says chemical engineer Liangfang Zhang from UC San Diego. "And we want to do it in a way that is safe, easy, biocompatible, and long-lasting."

"That is what we've demonstrated in this work."

The research has been published in Nature Materials.