As scientists continue to discover more about the brain and how it works, it can help to know just how much brain matter is required to perform certain functions – and to be able to make complex decisions, it turns out just 302 neurons may be required.

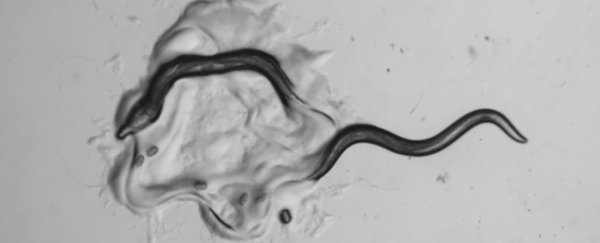

That's based on a new study looking at the predatory worm Pristionchus pacificus. To snack on its prey or to defend its food source, the worm relies on biting; this gave researchers an opportunity to analyze its decision-making.

Instead of looking at actual neurons and cell connections for signs of decision making, the team looked at the behavior of P. pacificus instead – specifically, how it chose to use its biting capabilities when confronted with different types of threat.

"Our study shows you can use a simple system such as the worm to study something complex, like goal-directed decision-making," says neurobiologist Sreekanth Chalasani from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California.

"We also demonstrated that behavior can tell us a lot about how the brain works."

In experiments, Chalasani and his colleagues observed P. pacificus taking two different strategies – biting to devour and biting to deter – with the Caenorhabditis elegans worm, both its prey and competitor.

With larval C. elegans that are easy to overpower, P. pacificus chose to bite to kill. With the adults, P. pacificus worms tended to bite to force C. elegans away from food sources. That's evidence of a switch in strategy and a deliberate choice.

By observing where P. pacificus worms laid their eggs, and how their behavior changed when a bacterial food source was nearby, the scientists determined that bites on adult C. elegans were intended to drive them away – in other words, they weren't simply failed attempts to kill these competitors.

While we're used to such decision making from vertebrates, it hasn't previously been clear that worms had the brainpower to proverbially weigh up the pros, cons, and consequences of particular actions in this way.

"Scientists have always assumed that worms were simple – when P. pacificus bites we thought that was always for a singular predatory purpose," says neuroscientist Kathleen Quach from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

"Actually, P. pacificus is versatile and can use the same action, biting C. elegans, to achieve different long-term goals. I was surprised to find that P. pacificus could leverage what seemed like failed predation into successful and goal-directed territoriality."

Having 302 neurons at your disposal isn't many, really – human beings have somewhere in the region of 86 billion of them. But it seems the fundamentals of decision-making are quite simple to code, biologically speaking.

One of the fields that this new research could help with is in the development of artificial intelligence: figuring out how to teach computer software to make independent decisions with as little programming and neural networking as possible.

Future research is planned to look at how much of this decision-making is hardwired into the brains of P. pacificus, and how much is flexible. Again, that will have implications when it comes to understanding how we make our own choices.

"Even simple systems like worms have different strategies, and they can choose between those strategies, deciding which one works well for them in a given situation," says Chalasani.

"That provides a framework for understanding how these decisions are made in more complex systems, such as humans."

The research has been published in Current Biology.