Titan, Saturn's largest moon, might have a more violent past than astronomers realised.

A new study suggests that the liquid methane lakes that dot Titan's surface may have formed when pockets of warming nitrogen exploded below the moon's surface.

This idea would solve a mystery that emerged when NASA's Cassini mission to Saturn – which launched in October 1997 and ended when the probe plunged into Saturn in September 2018 – sent back unprecedented data about these lakes.

Near the moon's north pole, the data showed, a series of small lakes sport rims that tower hundreds of feet above sea level. That surprised scientists, since the erosion process that formed other lakes on Titan couldn't have created those cliffs.

Blasts of exploding nitrogen, on the other hand, would have been powerful enough to create craters with tall rims of debris – which became the lakes we now see.

"This is a completely different explanation for the steep rims around those small lakes, which has been a tremendous puzzle," Linda Spilker, a Cassini scientist unaffiliated with the new study, said in a press release.

The study, published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience, provides new evidence that millions of years ago, Titan's frigid surface (it's -290 degrees Fahrenheit; -180 Celsius) was even colder – cold enough for liquid nitrogen to exist.

"These lakes with steep edges, ramparts, and raised rims would be a signpost of periods in Titan's history when there was liquid nitrogen on the surface and in the crust," Jonathan Lunine, a Cassini scientist who co-authored the study, said in a release.

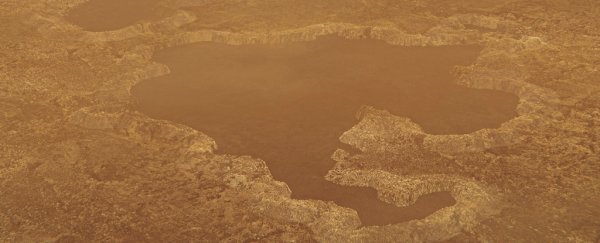

Illustration showing the raised rims of Titan's lakes. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Illustration showing the raised rims of Titan's lakes. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Warming after Titan's 'ice ages' could have caused explosions

Most of Titan's lakes are thought to have formed when liquid methane dissolved the moon's icy bedrock to sculpt reservoirs – similar to the way water has dissolved limestone to form lakes on Earth.

But the towering rims around these smaller lakes, which are dozens of miles wide, were confusing to scientists, since erosion wears rock away.

"In reality, the morphology was more consistent with an explosion crater, where the rim is formed by the ejected material from the crater interior. It's totally a different process," Giuseppe Mitri, who led the international team behind the study, said in the press release.

Scientists already knew that Titan has gone through periods of cooling and warming, as sunlight depleted the heat-trapping methane in its atmosphere, then methane later built up again. (Where exactly the new methane comes from is still a mystery.)

During Titan's "ice ages", scientists think nitrogen made up most of the moon's atmosphere, fell as liquid rain, and cycled through the world's icy crust, collecting in pools below the surface. This process is similar to Earth's water cycle.

But the new study suggests that, as the methane concentration got higher (today it's about 5 percent of Titan's atmosphere), the subsurface pockets of liquid nitrogen heated up vaporising into nitrogen gas. That process happened so rapidly, it released tremendous amounts of force, exploding under the surface and creating craters in Titan's surface."

Using radar data from Cassini's final flyby of Titan, Mitri's team found that the lakes' shapes do indeed look similar to that of craters made by explosions from the interaction of water and magma on Earth.

They also did the maths to show that the warming of liquid nitrogen below Titan's surface could create explosions big enough to form the lakes we see today.

What hydrocarbon ice forming on a hydrocarbon sea might look like on Titan. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS)

What hydrocarbon ice forming on a hydrocarbon sea might look like on Titan. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS)

Titan could harbour life in lakes or below its surface

Other than Earth, Titan is the only planetary body in our solar system that has stable liquid on its surface – though it's liquid ethane and methane, rather than water.

The planet is also saturated in carbon-rich organic compounds made from interactions between methane and nitrogen. Combined, these two factors indicate a potential for life to exist. (The lakes, rivers, and seas of methane and ethane would support a form of life very different from Earth's, though.)

Cassini also revealed an ocean of liquid water 60 miles below Titan's surface, which could provide a habitable, though very dark, environment for life.

Cassini, which spent 13 years exploring Saturn's system of rings and moons, was the first spacecraft to orbit the gas giant – it circled Saturn 294 times. Before Cassini, scientists didn't know about the liquid water that hides under the surfaces of Titan and its neighbouring moon, Enceladus.

Those discoveries have redefined scientists' search for extraterrestrial life. Now, NASA is planning a mission to study Titan's ocean and search for signs of life – past or present – using a nuclear-powered helicopter called Dragonfly. It's slated to launch in 2026 and arrive at Titan's surface in 2034.

In the meantime, scientists on Earth continue to investigate the moon using data from Cassini.

"As scientists continue to mine the treasure trove of Cassini data, we'll keep putting more and more pieces of the puzzle together," Spilker said. "Over the next decades, we will come to understand the Saturn system better and better."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: