Wherever cancer may lurk in the bowels of the human body, an engineered microbe could one day detect it.

That's the hope of an international team of researchers who have shown how, with a few instructions, one species of bacterium might expose bowel cancer as it forms in cell and animal models of the disease.

Although the approach is still years away from clinical trials, requiring more research to test its efficacy and safety, the idea of using modified microbes as diagnostic tools is not as out-there as you might think.

Our gastrointestinal tract is lined with bacteria, and scientists have been trying to harness the natural abilities of specific strains to make them work as probiotic sensors. These 'biosensors' have already shown promise in monitoring gut health and detecting intestinal bleeding, infections, and liver tumors – at least in mice and pigs.

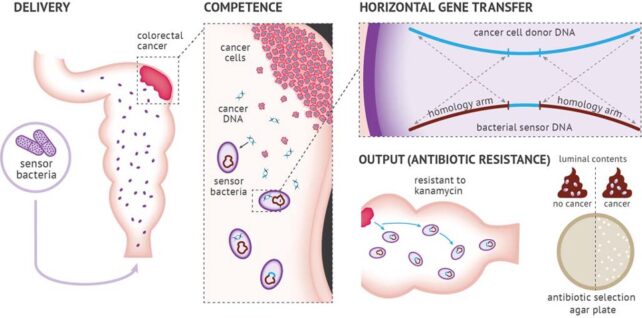

In this new study, a team led by biologist Robert Cooper at the University of California, San Diego, engineered bacteria to detect snippets of DNA shed from lab-grown colorectal cancer cells and mice harboring colorectal tumors.

"This study demonstrates how bacteria can be designed to detect specific DNA sequences to diagnose disease in hard-to-reach places," says biomedical scientist and study author Susan Woods of the University of Adelaide in Australia.

The researchers coopted Acinetobacter baylyi, a bacterial thief known for its ability to scoop up DNA from its environment.

Usually, A. baylyi uses this foraging ability (called natural competence) to incorporate chunks of DNA into its own genome that might provide new genetic recipes for handy proteins.

The researchers equipped A. baylyi with instructions to instead seek out specific mutation-carrying sequences commonly found in colorectal cancers. They found A. baylyi could discriminate the single-base difference between cancer-causing mutations and harmless genetic errors in free-floating DNA expelled from cells.

As you can see in the diagram below, the programmable system was designed so that if A. baylyi found any tumor DNA, incorporating the material into its own genome would switch on an antibiotic resistance gene. With it activated, A. baylyi extracted from the host's feces could grow on agar plates containing antibiotics – a signal that cancer cells had been detected.

"This shows that our biosensing system can be used to catch colorectal cancer DNA within a complex ecosystem, says Woods.

For now, the biosensor is designed to detect certain KRAS mutations, which are found in around 40 percent of colorectal cancers, as well as one-third of lung cancers, and most pancreas cancers.

Before its potential use in humans, researchers would need to show A. baylyi can be safely delivered orally and can reliably detect cancer cells in stool samples.

The sensitivity of the system – the level of free-floating tumor DNA A. baylyi can consistently detect – will determine how useful it is in the clinic, and if it could enable early detection of bowel cancer as researchers hope.

Researchers would also need to investigate how the A. baylyi biosensor compares to other, more invasive methods for detecting cancerous lesions, such as colonoscopy, which directly samples suspicious-looking cells.

Rates of bowel cancer are rising in people under 50, though cancer screening programs don't typically cover young adults.

The study has been published in Science.