Solar energy is off the charts. Not only is uptake skyrocketing, but solar is now the cheapest form of new energy in dozens of countries, with record-setting solar farms being built all around the world. One even looks like a giant panda.

But amidst the surge in all things solar, there's something we've been missing. When we think of solar panels, we tend to imagine the bulky units on people's rooftops or in large solar arrays – but there's another kind of solar technology in development, and it's virtually invisible.

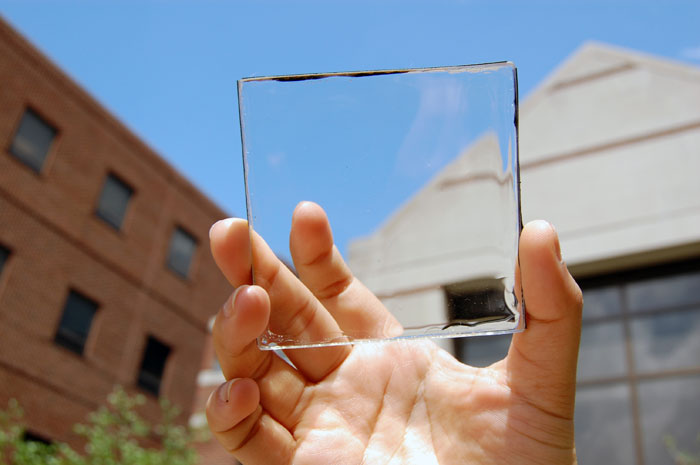

For years, researchers have been investigating ways to make transparent, see-through solar panels that effectively resemble glass, meaning we could use them as window panels at the same time as converting the light that shines on them into electricity.

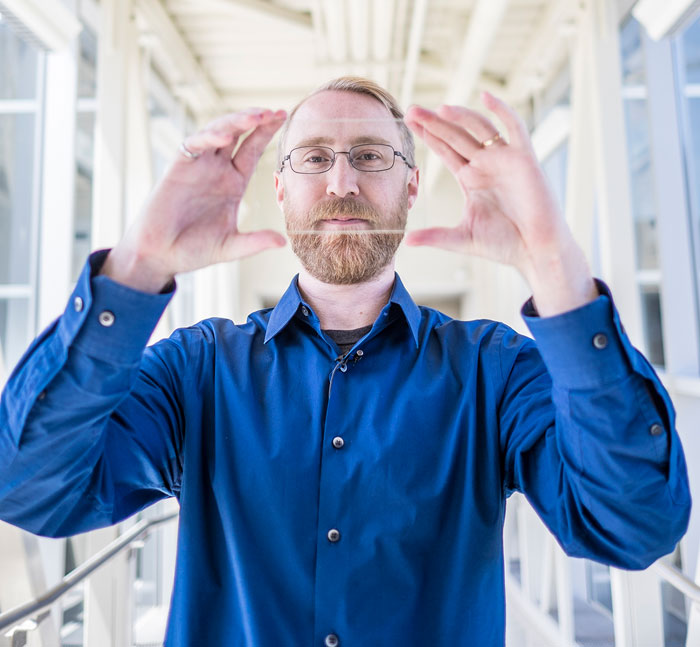

"Highly transparent solar cells represent the wave of the future for new solar applications," explains materials scientist Richard Lunt from Michigan State University.

"We analysed their potential and show that by harvesting only invisible light, these devices can provide a similar electricity-generation potential as rooftop solar while providing additional functionality to enhance the efficiency of buildings, automobiles, and mobile electronics."

Richard Lunt

Richard Lunt

Lunt ought to know a little about this kind of thing. In 2014 his team developed a transparent luminescent solar concentrator that looks just like a piece of clear glass, but which is covered in small organic molecules that can absorb specific invisible wavelengths of sunlight.

Because the material is tuned to capture just ultraviolet and near-infrared wavelengths of light, the visible light that enables human vision isn't obstructed, which is why we can see through the cell.

In their new study, Lunt and fellow researchers examined the efficiency of this kind of transparent solar tech, and estimate that if the see-through panelling can be scaled up to cover the estimated 5–7 billion square metres of glass surfaces throughout the US, it could potentially supply around 40 percent of American energy.

Last year, a similar analysis conducted by the Department of Energy suggested the rooftop solar potential of buildings in the US could satisfy about the same amount of power needs by using conventional panels.

By Lunt's math, the two types of cells – running in unison thanks to buildings sheathed virtually all over in solar capture materials – could effectively provide all the power the US needs, or at least within reach of that elusive goal.

"The complementary deployment of both technologies could get us close to 100 percent of our demand if we also improve energy storage," Lunt says.

And it's not just buildings that would stand to benefit.

Electric vehicles making use of transparent solar panels would be able to convert sunlight into extra mileage, while personal technology devices could use the same trick to extend their battery life.

It's a win-win, simply by surfaces around us absorbing the light we can't see anyway.

As it stands, Lunt says that transparent solar isn't yet as efficient as conventional solar panels, with efficiencies around 5 percent compared to the latter's 15–18 percent.

Kurt Stepnitz

Kurt Stepnitz

Luckily, there's an awful lot of windows in your average skyscraper, and as the technology develops, the efficiency is expected to get better – and we're going to need it to.

Right now, solar overall only provides a little over 1 percent of US power, and if we're ever going to truly kick fossil fuels to the curb, our use of solar technology, like the technology itself, needs to step up.

"That is what we are working towards," Lunt says.

"Traditional solar applications have been actively researched for over five decades, yet we have only been working on these highly transparent solar cells for about five years. Ultimately, this technology offers a promising route to inexpensive, widespread solar adoption on small and large surfaces that were previously inaccessible."

Awesome.

The findings are reported in Nature Energy.