New research has shown for the first time that trees don't just move water up and down like we previously thought - they can also move it across into their 'food tubes' to store it for a not-so-rainy day.

Scientists from the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at the University of Western Sydney in Australia have used fluorescent dyes to map the flow of water through trees, and found that the direction of movement isn't just vertical, its also horizontal.

It was previously assumed that plants transported food and water through two very separate pathways - the phloem and the xylem. The phloem transfers all nutrients, such as proteins and sugars, from the roots to the rest of the plant, and the xylem moves water upwards to the leaves.

But there was still something scientists couldn't work out - why, if the only water source is the xylem, don't more trees die out during hot, dry weather?

Water is able to move up even the tallest trees because the tiny xylem vessels maintain negative pressure. However, in times of drought, water bubbles can enter this system and cause the pressure to equalise. This is known as 'cavitation' and, although many plants can recover from it, it can lead to plant death through dehydration.

But, in theory, cavitation should kill a lot more plants than it does, so researchers hypothesised that there must be another place that plants could store and manage their water.

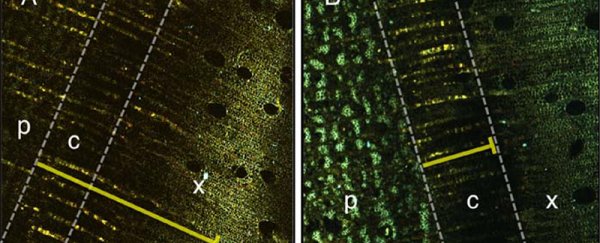

Now the team, working at the Hawkesbury Forest Experiment at the University of Western Sydney, has found the answer. Using microscopy and dyes, they've revealed that water can move at significant rates from the xylem to the phloem, and back again in Sydney Blue Gum trees. Their results have been published in the journal Plant Physiology.

They found that their dyes were more likely to travel from the xylem into the food-carrying phloem at night time, when there is more water available. The water is then stored in the phloem until the tree needs it, usually during the morning hours, when it travels back to the xylem via cells known as horizontal ray parenchyma cells, or simply 'wood rays'.

The Hawkesbury press release explains:

"What this means is that this research sheds new light on how trees actually do shift water into the phloem when they least need it (at night or during very humid or rainy weather) and then make use of it when they do need it in the xylem to maintain a continuous flow all the way up to the top of the tree."

We're just beginning to find out that plants are a whole lot smarter and more complex than we ever imagined, with researchers recently revealing that plants communicate with each other, recruit their own unique support community and can hear themselves being eaten by caterpillars.

We can't wait to learn more.

Love the environment? Find out more about studying at the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment.