Different models on the development of Parkinson's disease might represent a disease largely triggered by something in our environment, hinting at ways of preventing a significant number of cases.

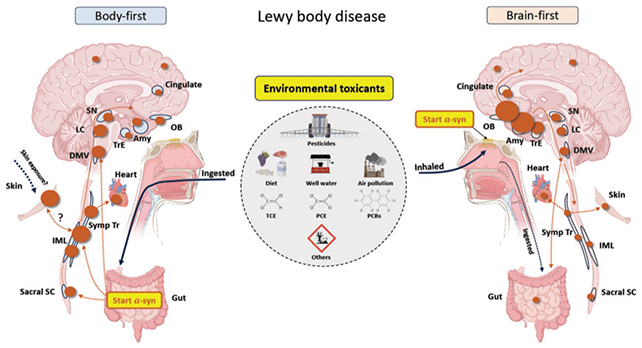

For some time, researchers have considered whether the gradual loss of neurons associated with Parkinson's primarily stems from olfactory nerves in the brain or nerves in the gut.

The compelling model proposed by an international team of researchers suggests the neurodegenerative condition could start with the spread of toxic proteins from either source, sparked by damage from environmental factors possible in both regions.

Ultimately, substances inhaled through the nose (hitting the brain's smell center) and ingested through the stomach could both be responsible for Parkinson's, the researchers say – and future studies should be able to make these connections clearer.

"In both the brain-first and body-first scenarios the pathology arises in structures in the body closely connected to the outside world," says neurologist Ray Dorsey from the University of Rochester Medical Center.

"Here we propose that Parkinson's is a systemic disease and that its initial roots likely begin in the nose and in the gut and are tied to environmental factors increasingly recognized as major contributors, if not causes, of the disease."

The team points the finger at dry cleaning and degreasing chemicals, air pollution, the use of herbicides, weed killer, and contaminated drinking water as some of the environmental toxicants that might potentially be triggering breakdowns in brain function.

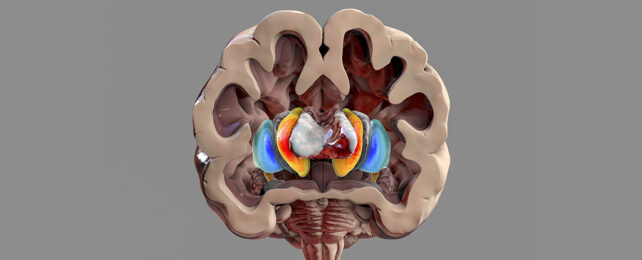

That is thought to happen through the misfolding of the alpha-synuclein protein, which then accumulates in clumps known as Lewy bodies. These clumps then take out many of the brain's nerve cells, including those in charge of motor control.

While this new study is only theoretical, it references links that have previously been confirmed between Parkinson's and numerous environmental hazards. However, picking apart these connections more precisely is going to take some time.

"These environmental toxicants are widespread and not everyone has Parkinson's disease," says Dorsey.

"The timing, dose, and duration of exposure and interactions with genetic and other environmental factors are probably key to determining who ultimately develops Parkinson's."

There are some unanswered questions with this new theory, the researchers admit, including what role the skin and microbiome might play, and how disease risk changes through prolonged exposures over time.

In fact, the exposures could often be happening years or even decades before the onset of Parkinson's symptoms – but approaching research into the disease using this new hypothetical model should help in determining if these links are indeed there.

"This further reinforces the idea that Parkinson's, the world's fastest growing brain disease, may be fueled by toxicants and is therefore largely preventable," says Dorsey.

The research has been published in the Journal of Parkinson's Disease.