Diabetes has afflicted humanity for thousands of years, but despite it being an old burden, we're still making major discoveries about how the illness actually manifests, as new research shows.

The distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes was drawn centuries ago, but the sub-categorisations don't end there. In a new study, researchers in the UK have found convincing signs to suggest that type 1 diabetes itself comprises two distinct sub-types: variations of the disease, called T1DE 1 and T1DE 2, that have never been conclusively identified before.

"We're extremely excited to find evidence that type 1 diabetes is two separate conditions," says endocrine pharmacologist Noel Morgan from the University of Exeter.

"The significance of this could be enormous in helping us to understand what causes the illness, and in unlocking avenues to prevent future generations of children from getting type 1 diabetes."

Diabetes is an inability to maintain healthy levels of glucose in the blood, with the illness primarily manifesting in two major forms.

Type 1 diabetes is a life-long condition that's usually diagnosed in children and young people. Type 2 diabetes, which is far more common and largely preventable (even reversible), is usually identified in adults, and is influenced by both lifestyle and genetic factors.

At least, that's long been the thinking; but in recent years, researchers have found evidence that these classifications need further examination. Other new types of diabetes are being discovered, and researchers have found that type 2 diabetes may be more complex than we realised.

The latest research suggests type 1 diabetes also represents more than one condition – a distinction that appears to be defined by the age of patients receiving their type 1 diabetes diagnosis.

Previous research by some of the same team in 2014 and 2016 had suggested different immunopathological processes might underlie type 1 diabetes, suggesting different endotypes of the disease may exist. Now that hypothesis has additional weight behind it.

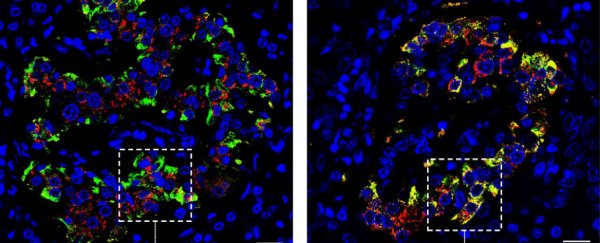

In the new study, researchers analysed a sample of approximately 130 pancreas samples taken from children and young people with recent-onset type 1 diabetes. The results showed "two strikingly different patterns" with regard to the amount of proinsulin: the insulin hormone precursor that's produced in the pancreas.

In children younger than seven at the time of their diagnosis, the proinsulin wasn't processed properly, and was released from the hormone-producing cell clusters known as pancreatic islets alongside insulin - a sign that not enough of the precursor is being turned into the insulin that the body needs.

By contrast, in samples taken from patients aged 13 and over at the time of their diagnosis, proinsulin and insulin weren't co-localised like this, suggesting more normalised production of the hormone.

Additionally, in both endotypes we also see the autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing cells in the pancreatic islets, but at different rates - as per the results of previous research, in children younger than seven that destructive process happens more aggressively.

"Our results strongly suggest that type 1 diabetes exists as distinct conditions that segregate according to age at diagnosis and are distinguishable histologically," the researchers explain in their study.

"We propose that these may represent disease endotypes and suggest that they are defined as type 1 diabetes endotype 1 (T1DE1) and type 1 diabetes endotype 2 (T1DE2)."

(Leete et al., Diabetologia, 2020)

(Leete et al., Diabetologia, 2020)

Above: Fluorescence micrographs showing: on left, islet in which proinsulin and insulin are segregated (T1DE2); on right, islet with aberrant proinsulin processing (T1DE1).

T1DE1, indicative of disruption of insulin processing, is the endotype found among children seven years or younger when diagnosed, while T1DE2 is the endotype found in children aged 13 or older. The researchers say children who are diagnosed while in between seven and 13 could have either endotype.

"We do not intend to imply that a simple dichotomy will ultimately be sufficient to account for the entire heterogeneity seen in people developing type 1 diabetes," the researchers write.

"Rather, it is probable that additional endotypes will be defined as further variables are considered."

Quite where that possibility will lead us remains a question for future research, and the findings so far may also need to be replicated in larger studies with more patient samples, to help fortify the discovery of the endotypes identified so far.

For now, though, the team says the age of the patient at the time of type 1 diabetes diagnosis could be an important clue as to what their particular endotype and resulting pathology may be – bringing us closer to a day where we might be able to tailor diabetes treatments to T1DE1, T1DE2, and whatever other variations researchers might eventually uncover.

"The era of being able to halt the immune attack behind type 1 diabetes is in reach, but to make new treatments as effective as possible we need to really get to grips with the complexity of the condition," says Elizabeth Robertson, director of research at Diabetes UK, which helped fund the study.

"Today's news brings us one step closer to achieving that."

The findings are reported in Diabetologia.