Tyrannosaurus rex might not have been puckering up for a good ol' snog, but the dinosaur's teeth were not exposed like a 'gator's; instead, they protected behind a pair of lizardy lips.

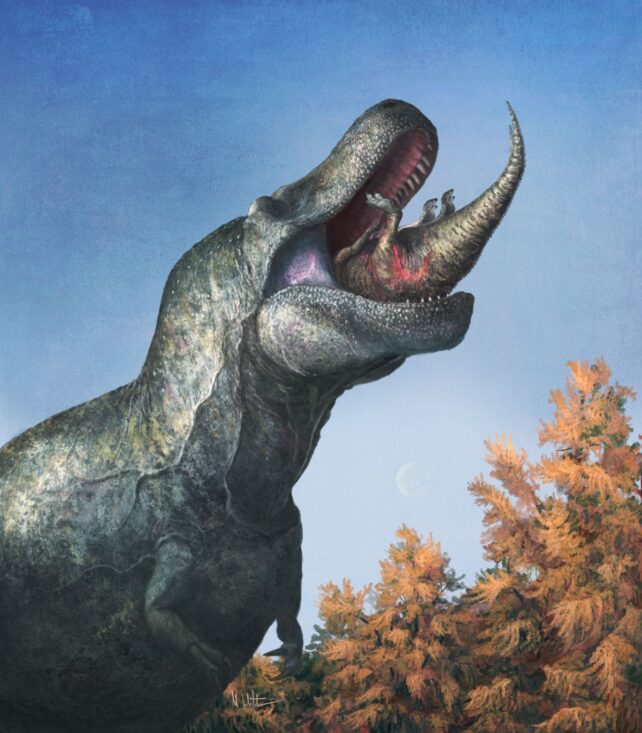

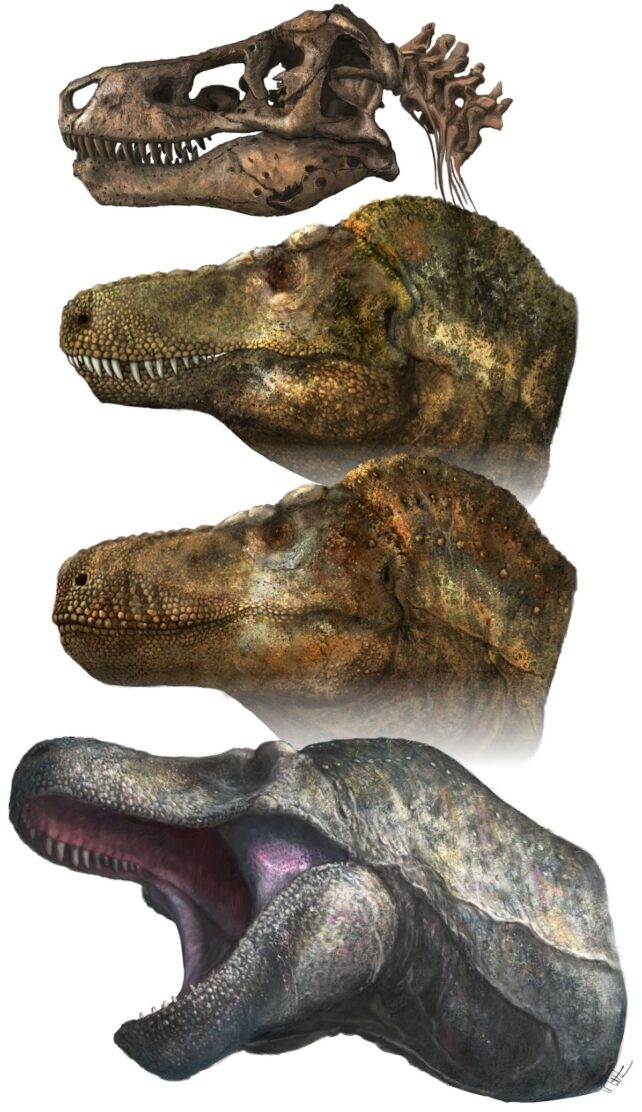

That's the result of work investigating the teeth and bones of reptiles and dinosaurs, present and past, finally resolving a long-standing debate in paleontology. Paleoartists can now complete the grins of T. rex and its theropod cousins with thin, scaly lips, and paleontologists can better understand the bones these dinosaurs left behind.

"Dinosaur artists have gone back and forth on lips since we started restoring dinosaurs during the 19th century, but lipless dinosaurs became more prominent in the 1980s and 1990s. They were then deeply rooted in popular culture through films and documentaries – Jurassic Park and its sequels, Walking with Dinosaurs, and so on," explains paleontologist and paleoartist Mark Witton of the University of Portsmouth in the UK.

"Curiously, there was never a dedicated study or discovery instigating this change and, to a large extent, it probably reflected preference for a new, ferocious-looking aesthetic rather than a shift in scientific thinking. We're upending this popular depiction by covering their teeth with lizard-like lips. This means a lot of our favorite dinosaur depictions are incorrect, including the iconic Jurassic Park T. rex."

Most of the dinosaur fossils we've retrieved, including the theropod group that includes T. rex, are incomplete, consisting primarily of bones. Dinosaur skin is rarely preserved, and what we get is usually patchy and incomplete. We know, from preserved T. rex skin, that these dinosaurs were scaly rather than feathered, but the detailed particulars are impossible to ascertain from these samples.

So, an international team of researchers led by paleobiologist Thomas Cullen of Auburn University in the US went looking at the resource we do have: bones.

Their work consisted of a detailed comparative analysis of the differences in the teeth and skull bones of lipped and lipless reptiles, including monitor lizards, marine iguanas, and alligators. They studied the tooth structure, wear patterns, and jaws of several reptiles in these groups and put together the set of characteristics of each.

Then, they applied that understanding to fossils, not just of theropods like T. rex, but extinct early crocodilians. And they found that the mouth anatomy of T. rex was a lot closer to that of lipped reptiles.

"It's quite remarkable how similar theropod teeth are to monitor lizards. From the smallest dwarf monitor to the Komodo dragon, the teeth function in much the same way," explains paleontologist Derek Larson of the Royal BC Museum in Canada.

"So, monitors can be compared quite favorably with extinct animals like theropod dinosaurs based on this similarity of function, even though they are not closely related."

In particular, the wear patterns on the teeth of reptiles without lips significantly differ from those of carnivorous dinosaurs. Crocodilian teeth tend to be more easily damaged during fighting and feeding, a trait linked to the lack of protection from saliva in a closed mouth. The teeth of the dinosaurs in the team's study did not show wear consistent with this type of damage.

And although T. rex teeth were larger than those of modern reptiles, that size was proportional to those of our present-day predatory lizards when considering the size of their skulls to their teeth.

"Although it's been argued in the past that the teeth of predatory dinosaurs might be too big to be covered by lips, our study shows that, in actuality, their teeth were not atypically large," Cullen says.

"Even the giant teeth of tyrannosaurs are proportionally similar in size to those of living predatory lizards when compared for skull size, rejecting the idea that their teeth were too big to cover with lips."

The shape of the skull and animated computer models of the skull, too, show that the T. rex jaw would have had difficulty closing fully without lips.

Put together, this information seems to imply that T. rex had a mouth that closed over its teeth, complete with thin, scaled lips. These would not have been mobile and muscular, like mammal lips, but they would have helped protect the dinosaur's teeth, and that – at least in this respect – T. rex was more like lipped lizards than alligators or birds.

It's a finding that has important implications for our understanding of how these beasts lived their lives: how their jaws worked, how they ate, and how they hunted. For example, teeth more resistant to damage on striking bone could mean that the dinosaurs were able to munch more of their kills than if their teeth were more brittle.

And we have another piece of the "what did T. rex actually look like" puzzle.

"Some take the view that we're clueless about the appearance of dinosaurs beyond basic features like the number of fingers and toes," Witton says.

"But our study, and others like it, show that we have an increasingly good handle on many aspects of dinosaur appearance. Far from being clueless, we're now at a point where we can say, 'Oh, that doesn't have lips? Or a certain type of scale or feather?' Then that's as realistic a depiction of that species as a tiger without stripes."

The research has been published in Science.