Icy materials in space could behave like liquids at low temperatures and under ultraviolet light, suggests new research, and that might help to explain how planets began to form in the earliest days of the Solar System.

The gas and icy giants circling round our Sun are thought to have been created from water-dominated ice, and the behaviour observed in the new study gives us one scenario as to how that might have happened.

According to the researchers from Hokkaido University in Japan, when the deep space conditions are right, this particular type of ice can attract and hold dust and debris, starting off a chain reaction that ends up with something like Jupiter.

"The liquid-like ice may help dust accrete to planets because liquid may act as a glue," says lead researcher Shogo Tachibana. "However, further experiments are needed to understand the material properties of the liquid-like ice."

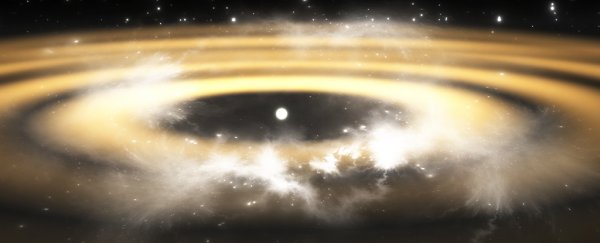

Ice bubbling under ultraviolet light. Credit: Tachibana et al., Sci. Adv. 2017

Ice bubbling under ultraviolet light. Credit: Tachibana et al., Sci. Adv. 2017

To mimic interstellar conditions, Tachibana and his colleagues sprayed a mixture of water, methanol and ammonia onto a substrate, chilling it to between -263°C (-441°F) and -258°C (-432°F), and dousing it in ultraviolet light.

After the ice had formed, the scientists slowly raised the temperature and observed it under a microscope. At temperatures between -210°C (-346°F) and -120C (-184°F), it bubbled like boiling water, with a viscosity similar to honey.

Based on the hydrogen molecules observed in the gas, the researchers think the reaction was caused by methanol and ammonia being broken up by UV irradiation. As the hydrogen bonds are rearranged, the ice's viscosity is lowered at the same time.

All of which means that this bubbling, honey-style ice could have grabbed passing space dust as our Solar System was coming into being, quickly forming planets from the protoplanetary disks circling the new Sun, as the star beamed out UV radiation.

Follow-up tests using pure water also showed liquid-like behaviour occurred when ultraviolet light was applied at very low temperatures, backing up the idea that this liquid-like state could be common in water-based ice.

However, fewer bubbles were present in ice with higher water content, and when the UV light was taken away, the bubbling stopped altogether.

What's more, the researchers say that these same reactions could also be responsible for creating just the right environment for organic molecules to form, the very first building blocks needed for life to start.

It's still early days for this area of research, but the tests could point to one of the most important chemical reactions for the formation of planets and life out in space.

"The formation of organic molecules, including prebiotic ones, may efficiently occur in a very cold environment," says Tachibana.

The research has been published in Science Advances.