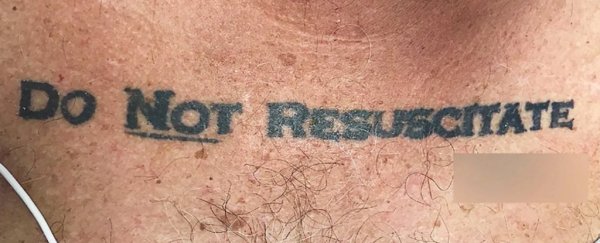

Doctors in Miami faced an unusual ethical dilemma when an unconscious, deteriorating patient was brought into the emergency room with the words "Do Not Resuscitate" across his chest.

The 70-year-old man was taken earlier this year to Jackson Memorial Hospital, where doctors made their startling discovery: a chest tattoo that seemed to convey the patient's end-of-life wishes. The word "Not" was underlined, and the tattoo included a signature.

It left the medical team grappling with myriad ethical and legal questions.

Was it an accurate representation of what the patient wanted? Was it legally sound? Should they honor it?

The case was detailed Thursday in the New England Journal of Medicine, in a report that laid out the medical team's struggle for answers.

"This patient's tattooed DNR request produced more confusion than clarity, given concerns about its legality and likely unfounded beliefs that tattoos might represent permanent reminders of regretted decisions made while the person was intoxicated," the paper's authors wrote.

Gregory Holt, a critical-care physician and lead author of the paper, said in an interview that "I think a lot of people in medicine have joked around about getting such a tattoo - and then when you finally see one, there's sort of this surprise and shock on your face. Then the shock hits you again because you actually have to think about it."

Holt said the patient, who had a history of pulmonary disease, lived at a nursing home but was found intoxicated and unconscious on the street and brought to Jackson Memorial.

He arrived with no identification, no family or friends, and no way to tell doctors whether he wanted to live or die.

Holt said the man had an infection that led to septic shock, which causes organ failure and extremely low blood pressure.

When his blood pressure started to drop, emergency room doctors called Holt, who specializes in pulmonary disease - and they first agreed not to honor the tattoo, "invoking the principle of not choosing an irreversible path when faced with uncertainty," according to the case study.

They gave the man intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and blood-pressure medication to buy themselves more time to make the life-or-death decision.

The medical team used a breathing mask on the man, Holt said, but struggled the most with the decision to hook him up to a machine that would breathe for him.

"We had a man I couldn't talk to," Holt told The Washington Post, "and I really wanted to talk to him to see whether that tattoo truly reflected what he wanted for his end of life wishes."

Doctors treating the elderly patient knew of "a cautionary tale" published in 2012 in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

That paper told of a 59-year-old patient who had a "D.N.R." tattoo across his chest but said he wanted lifesaving measures to be taken, in the event that he needed them.

When the patient was asked why he had the tattoo, he told doctors he had "lost a bet playing poker," according to the report.

Florida requires do-not-resuscitate orders to be printed on yellow paper and signed by a physician, so doctors at Jackson Memorial called an ethics consultant to discuss the legal aspects of the tattoo.

Holt said the consultant determined doctors didn't need to be entirely "dogmatic" and could presume the tattoo was an accurate reflection of the patient's wishes.

After reviewing the patient's case, the ethics consultants advised us to honor the patient's do not resuscitate (DNR) tattoo. They suggested that it was most reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference, that what might be seen as caution could also be seen as standing on ceremony, and that the law is sometimes not nimble enough to support patient-centred care and respect for patients' best interests.

In any case, social workers were later able to track down the man's proper DNR paperwork, leaving doctors relieved, Holt said.

The man, who was never publicly identified, died the next morning.

Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics and head of the division of medical ethics at the New York University School of Medicine, said a DNR tattoo is not a substitute for an advance health-care directive, or living will.

"A tattoo, I think, is best seen as a way to alert medical staff to your wishes or trigger an inquiry to family and friends and partners: 'Is that what he meant?'" he said, adding that patients should keep the actual document in a pocket or wallet.

"It's useful to back up a living will or an advanced directive."

There are no legal penalties for ignoring a tattoo that instructs medical personnel not to resuscitate, Caplan said.

On the other hand, he said, letting a patient die without the legal documents to back it up could pose a problem.

"The safer course is to do something," he said. But, he added, doctors routinely have to make difficult decisions.

Caplan said patients should also make sure their families and friends are aware of their wishes.

If a family member or friend calls 911, Caplan said, the emergency medical technicians are going to resuscitate the patient.

"If you trigger the emergency response system, I'm going to say it's pretty darn likely you're going to get resuscitated - I don't care where your tattoo is," Caplan said.

Holt, the doctor at Jackson Memorial, said his patient's tattoo seemed like a serious request, and doctors honored it.

"It also seemed that he didn't trust that his end-of-life wishes would be conveyed appropriately," he said of the patient. "So, to me, it means we need a better system.

"We need a better system for people to be able to convey their wishes - if these are their wishes - so that we don't do things to them that they don't want, like in the throes of an emergency when a man like this comes into the emergency room unconscious."

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.