While some still quibble over wearing masks a year into the pandemic, scientists have gotten on with working out exactly what strategy is best - and cotton face masks just received another tick of approval.

Various studies have tested different material combinations and health authorities such as the World Health Organization and the CDC recommend cloth masks for the general public, based on their conclusions. But some of these studies overlooked an important real-world factor - these face covering fabrics end up damp from our breath.

Now, a team of researchers has tested mask materials under high humidity conditions that mimic the air expelled from our mouths.

"This new study shows that cotton fabrics actually perform better in masks than we thought," said material scientist Christopher Zangmeister from the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

Zangmeister and colleagues tested nine different types of cotton and six types of synthetic fibers including polyester and rayon in 99 percent humidity (about how humid our breath is) and 55 percent humidity.

This resulted in a remarkably visible difference in the performance of cotton.

Cotton masks become better filters when they absorb the moisture from your breath, making them even better at slowing COVID-19 than we thought: https://t.co/qbGtnC4a42 pic.twitter.com/91hNVIvlTX

— National Institute of Standards and Technology (@NIST) March 9, 2021

While synthetic fabrics, which also performed poorly compared to dry cotton, did not change performance under humid conditions, cotton fabrics increased their ability to capture particles by 33 percent.

The researchers used variously sized particles of salt as a test substitute for virus-transporting droplet and aerosol particles,and these appeared to absorb some of the moisture trapped by the water-attracting cotton fibers. The particles swell in volume, which makes it harder for them to pass through the fabric uninhibited.

Synthetic fibers, however, repel water, thus not creating the humid environment within the mask itself for this inhibition to happen. There was also no change in medical masks - but they are designed to work at high levels in all conditions (equivalent levels to cotton).

The best-performing type of cotton was cotton flannel, according to the results.

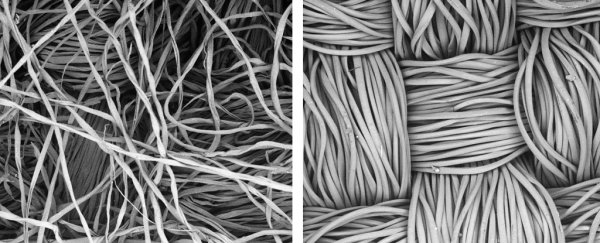

Microscopic images of the materials reveal a stark difference in structure - an orderly weave pattern in synthetic polyester compared to the chaotic network of crisscrossing fibers that give flannel its soft-to-touch feel.

NIST researchers believe this mess of fibers is what increases the chance airborne particles passing through the mask will collide and stick to the fabric.

Cotton flannel (left), polyester (right). (E.P. Vicenzi/Smithsonian Museum/NIST)

Cotton flannel (left), polyester (right). (E.P. Vicenzi/Smithsonian Museum/NIST)

However, all this doesn't mean wet masks are better: If your mask gets wet, it should be replaced. The amount of liquid present in the masks in these humid conditions amounts only to a few drops, which doesn't alter the material's breathability - the team found air pressure on both sides of the fabric remained relatively similar.

This is great news from an environmental perspective too. With mounting waste from disposable surgical masks that shed microplastics, it's comforting to know there's a safe, reusable option.

Research suggests owning a bunch of reusable masks that can be machine-washed together is the most eco-friendly option to keep you and your loved ones safe.

While the team says more research is required to fully appreciate the interactions between masks, humidity, and aerosol particle transmission, their study has contributed to the first international standards for fabric masks meant to slow the spread of COVID-19, recently released by the standards-developing organization ASTM International.

"To understand how these materials perform in the real world we need to study them under realistic conditions," Zangmeister concluded.

This research was published in ACS Applied Nano Materials.