Originally, they were thought to be just specks of dust on a microscope slide.

Now, a new study suggests that microchromosomes – a type of tiny chromosome found in birds and reptiles – have a longer history, and a bigger role to play in mammals than we ever suspected.

By lining up the DNA sequence of microchromosomes across many different species, researchers have been able to show the consistency of these DNA molecules across bird and reptile families, a consistency that stretches back hundreds of millions of years.

What's more, the team found that these bits of genetic code have been scrambled and placed on larger chromosomes in marsupial and placental mammals, including humans. In other words, the human genome isn't quite as 'normal' as previously supposed.

"We lined up these sequences from birds, turtles, snakes and lizards, platypus and humans and compared them," says geneticist Jenny Graves, from La Trobe University in Australia. "Astonishingly, the microchromosomes were the same across all bird and reptile species.

"Even more astonishingly, they were the same as the tiny chromosomes of Amphioxus – a little fish-like animal with no backbone that last shared a common ancestor with vertebrates 684 million years ago."

By tracing these microchromosomes back to the ancient Amphioxus, the scientists were able to establish genetic links to all of its descendants. These tiny 'specks of dust' are actually important building blocks for vertebrates, not just abnormal extras.

It seems that most mammals have absorbed and jumbled up their microchromosomes as they've evolved, making them seem like normal pieces of DNA. The exception is the platypus, which has several chromosome sections line up with microchromosomes, suggesting that this method may well have acted as a 'stepping stone' for other mammals in this regard, according to the researchers.

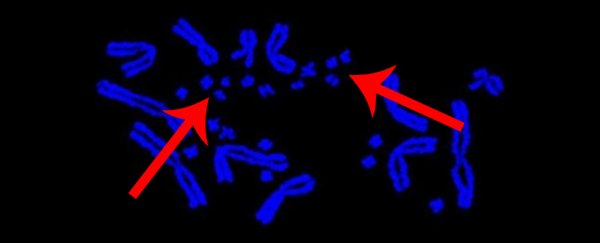

Microchromosomes are consistent in birds and reptiles, but mixed up in larger chromosomes in mammals. (Paul Waters)

Microchromosomes are consistent in birds and reptiles, but mixed up in larger chromosomes in mammals. (Paul Waters)

The study also revealed that as well as being similar across numerous species, the microchromosomes were also located in the same place inside cells.

"Not only are they the same in each species, but they crowd together in the center of the nucleus where they physically interact with each other, suggesting functional coherence," says biologist Paul Waters, from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia.

"This strange behavior is not true of the large chromosomes in our genomes."

The researchers credit recent advancements in DNA sequencing technology for the ability to sequence microchromosomes end-to-end, and to better establish where these DNA fragments came from and what their purpose might be.

It's not clear whether there's an evolutionary benefit to coding DNA in larger chromosomes or in microchromosomes, and the findings outlined in this paper might help scientists put that particular debate to rest – although a lot of questions remain.

The study suggests that the large chromosome approach that has evolved in mammals isn't actually the normal state, and might be a disadvantage: genes are packed together much more tightly in microchromosomes, for example.

"Rather than being 'normal', chromosomes of humans and other mammals were puffed up with lots of 'junk DNA' and scrambled in many different ways," says Graves.

"The new knowledge helps explain why there is such a large range of mammals with vastly different genomes inhabiting every corner of our planet."

The research has been published in PNAS.