With the right mechanical contraption attached, human running speeds could rival those of cyclists, according to new research – getting runners up to 20.9 metres per second, or more than 46 miles per hour.

It's worth noting that these are theoretical calculations for now, and the team responsible is hoping to have their prototype ready next year. The figures are based on the potential that would be released by a spring-based, catapult-like exoskeleton attachment.

We've seen these sorts of exoskeletons used in the past to help paralysed people, and a working device could have a lot of potential uses – though any Olympic records set using it would be unlikely to stand.

"Our result may lead to a new-generation of augmentation devices developed for sports, rescue operations, and law enforcement, where humans could benefit from increased speed of motion," write the researchers in their published paper.

The mechanics themselves are actually based on bicycles: bike pedals are so effective because they help us propel ourselves forward while our feet are pulling up, as well as when they're pushing down. This is energy that's wasted while we're running.

Even the fastest runners on Earth aren't gaining any speed once their feet leave the ground – only when their feet hit the track and push off. And as runners get faster, their feet spend more time in the air.

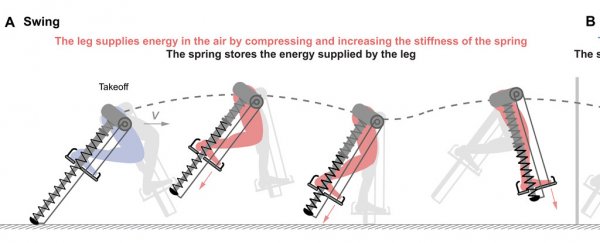

So how could this 'wasted' time be better used? The researchers behind the new study looked at a variety of concepts, landing upon a spring-based attachment that works a little like a catapult to shoot a runner forward.

"The disparity between cycling mechanics and running mechanics gave us the idea to hypothesise a device that allows the legs to do work in the air," mechanical engineer David Braun, from Vanderbilt University, told Emma Betuel at Inverse.

The idea of attaching springs to legs has been around for more than a century, but it's not particularly efficient by itself. In this case, the team used computer modelling to hit upon a device where the spring is storing energy until the foot hits the ground again.

How the device would work. (Sutrisno & Braun, Science Advances, 2020)

How the device would work. (Sutrisno & Braun, Science Advances, 2020)

That energy would come from the leg bending and moving forward in the air, the researchers suggest. The spring could release that energy on contact with the ground, as well as adding more support to the body.

To reach the top speeds, the analysis shows, the spring would need to capture energy for 96 percent of the step, and be able to transfer it all to forward acceleration. The 20.9 metres-per-second figure is also based on the energy pumped out by a world-class cyclist, so the rest of us might be a little slower.

Plenty of challenges remain – not least dealing with the extra impact each step would have coming down from a greater height – but the researchers suggest the spring could be programmed to adjust itself to different speeds, like the gears on a bike.

As well as helping emergency services, rescue workers and just about anyone else who needs to get somewhere fast, an exoskeleton like this might even inspire a brand new sport (just like bicycles did), say the researchers. In time, they hope the entire device might even fit inside a shoe.

"This shows us how far we can push the boundaries and what key features we should focus on to develop the new technology," Braun told Ian Sample at The Guardian.

The research has been published in Science Advances.