As medical laboratories around the globe push limits to develop a vaccine that could end a pandemic once and for all, an even harder challenge awaits – getting it to where it can do the most good.

Ten years ago, an international team of researchers established the Vaccine Confidence Project (VCP) in order to clarify global attitudes regarding the safety and efficacy of vaccination.

While vaccination uptake itself is closely monitored around the world by groups like the World Health Organisation (WHO), our understanding of the cultural trends behind the decision process is threadbare at best.

To address this shortfall in data, the VCP analysed hundreds of surveys and tens of thousands of interviews collected between 2015 and 2019, providing vital information on the vaccination beliefs of more than 284,000 people across 149 countries.

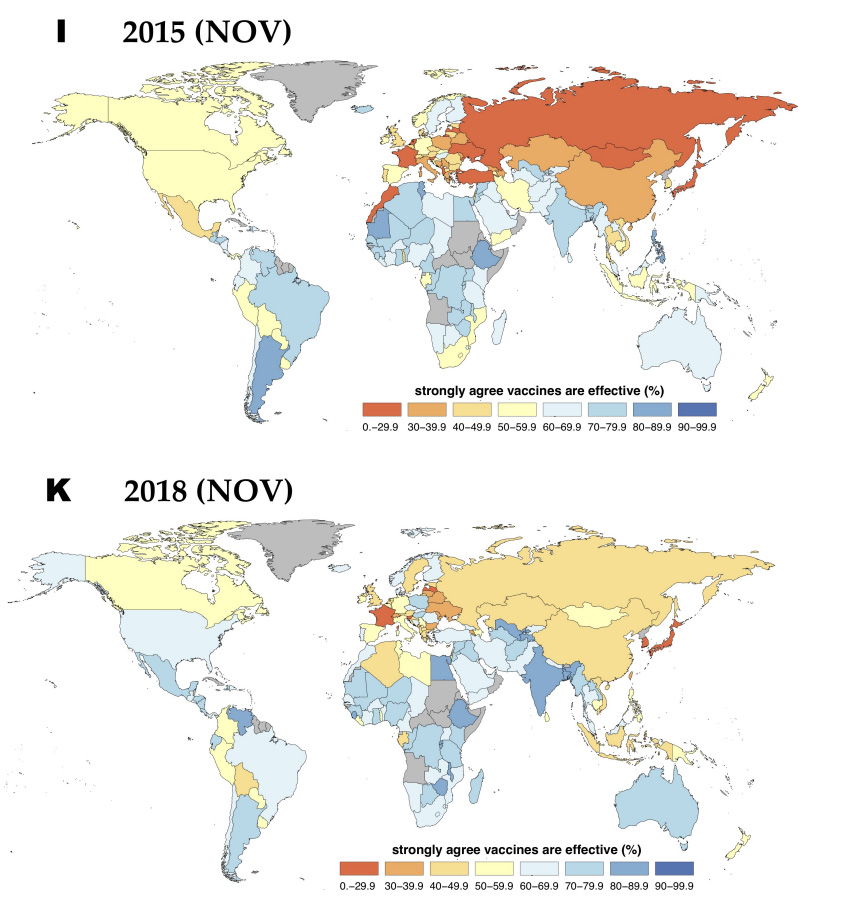

The study's results provide us with a global map of rising and falling confidence in the overall safety and general effectiveness of vaccines and the perceived importance of vaccinating children.

The researchers also collected demographic details to combine with the survey's results, allowing them to model relationships between vaccine uptake and factors such as religious belief, socioeconomic status, and even sources of trust.

The result is an atlas of mounting fears, growing trust, and indications of troubling viral hotspots in years to come.

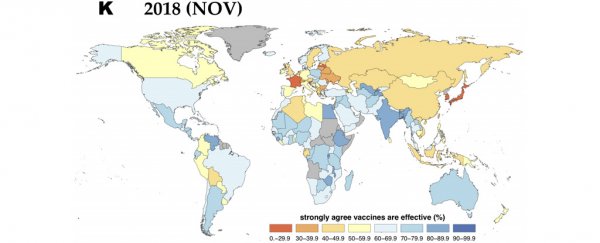

(de Figueiredo, et al., The Lancet, 2020/Appendix 1)

(de Figueiredo, et al., The Lancet, 2020/Appendix 1)

Across the European Union, attitudes are waxing and waning. Just two years ago, 64 percent of Polish citizens strongly agreed that vaccines are safe. A year later the number had dropped by one in ten to 53 percent.

There's reason to be optimistic though. In France, confidence in vaccines has been notably low in recent years, with a mere one in five agreeing to their safety in 2018. By the end of 2019, this had improved to nearly one in three.

Similar improvements have been seen in other places around Europe and the UK, including Finland, Italy, and Ireland. In fact, by the end of last year, most of the EU's confidence in vaccines had climbed.

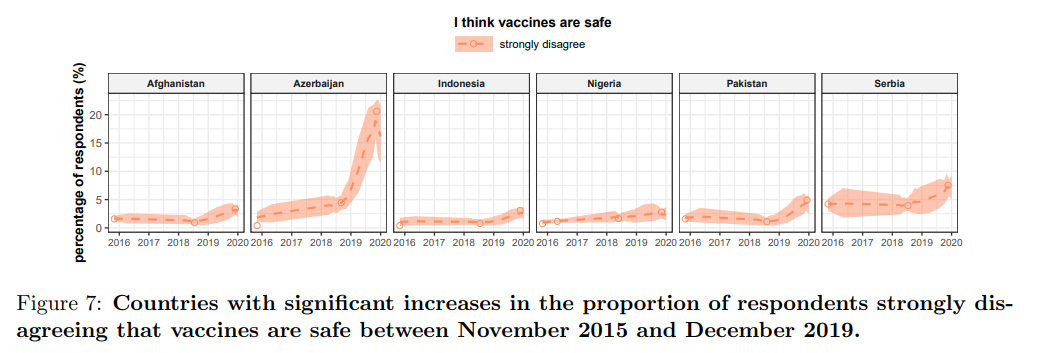

Further to the east, things aren't looking quite as promising. In 2015, a mere 2 percent of people in Azerbaijan strongly disagreed that vaccines were safe. This jumped to a shocking 17 percent by late 2019.

Afghanistan, Indonesia, and Pakistan all had similarly small figures of 1 to 2 percent disagreeing in vaccine safety, with less significant jumps to 3 to 4 percent over a similar period.

Though not as alarming as Azerbaijan's plummeting confidence level, community safety is a numbers game, where a reluctant few can make the difference between the eradication of a virus and its persistence in pockets of sustained infection.

(de Figueiredo, et al., The Lancet, 2020/Appendix 1)

(de Figueiredo, et al., The Lancet, 2020/Appendix 1)

Above: Model-based estimates of the percentage of respondents strongly agreeing that vaccines are effective in November 2015 and November 2018. No data were available for countries in grey.

Links between demographic details and vaccine confidence could provide health workers with better ideas of who to engage, and how to go about changing perspectives. Men, for example, were less likely to vaccinate themselves. So were those with limited education.

In some cases the cause of a loss in confidence can be traced to specific events. For example, fears and confusion over a Dengue virus vaccine called Dengvaxia, controversially rolled out in 2017, seem to be behind a dramatic fall in vaccine confidence in the Philippines. In 2015 they were in the top 10 most confident countries, with 82 percent strongly agreeing they were safe. By 2019, this had fallen to 58 percent.

In countries like Indonesia, religious authorities can heavily influence public opinion over vaccination programs and their safety.

Beyond the raw statistics there are subtle details on how these attitudes might affect behaviours, such as vaccinating children.

"Our findings suggest that people do not necessarily dismiss the importance of vaccinating their children even if they have doubts about how safe vaccines are", says Clarissa Simas, a psychologist from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK.

"The public seem to generally understand the value of vaccines, but the scientific and public health community needs to do much better at building public trust in the safety of vaccination, particularly with the hope of a COVID-19 vaccine."

Much has changed in recent months, of course. Attitudes are evolving almost weekly as misinformation is amplified by social media, and hopes and fears compete amid a global health catastrophe.

Which is all the more reason to build a clear foundation of knowledge on how people around the world come to change their minds on public health.

"It is vital with new and emerging disease threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic, that we regularly monitor public attitudes to quickly identify countries and groups with declining confidence, so we can help guide where we need to build trust to optimise uptake of new life-saving vaccines", says VCP director Heidi Larson, an anthropologist from the London school of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK.

In many ways, delivering vaccines is as much a scientific problem as their creation. Brute force isn't going to cut it, so we're going to need informed strategies of public engagement to build trust in healthcare.

Thankfully humanities are making headway in the understanding of the diverse and complex forces at work in our minds as we weigh up the pros and cons of vaccination.

To inform them, we're going to need more studies like this one.

This research was published in The Lancet.