Almost on the cusp of the Mariana Trench, before it plunges down into the very bowels of the ocean, scientists have found something rare and wonderful. Sometime in 2015, an underwater volcano experienced a massive eruption, spewing molten magma into the surrounding ocean.

As the incredibly hot magma meets the water, it begins to rapidly cool. The result? A vast field of volcanic glass. And, even more spectacularly, at a depth of 4,050-4,450 metres (2.51 to 2.76 miles) it's the deepest known volcanic eruption ever found on Earth.

This large field of volcanic glass stretches 7.3 kilometres (4.5 miles) along a region known as the Mariana Trough, a back-arc basin associated with the active volcanic arc that runs along the lip of the Mariana Trench.

Since this region sits right on the edge of a subduction zone, where the edge of one tectonic plate slips under another, volcanic activity is not unexpected, nor even uncommon. But studying this activity isn't easy.

"We know that most of the world's volcanic activity actually takes place in the ocean, but most of it goes undetected and unseen," said marine geologist Bill Chadwick of Oregon State University and NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

"Undersea quakes associated with volcanism are usually small, and most of the instrumentation is far away on land. Many of these areas are deep and don't leave any clues on the surface. That makes submarine eruptions very elusive."

The video below shows the first time one of these underwater eruptions was caught on film, released in 2009 - less than 10 years ago.

The deepest known eruption, which is now the subject of a new research paper, was first noted in December 2015, by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute's autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry.

At that time, the volcanic glass flows looked pristine. Nothing was growing on them, and no sediment had started to cover them. A nearby hydrothermal vent was also seeping milky fluid, an indication that the lava flow was still warm.

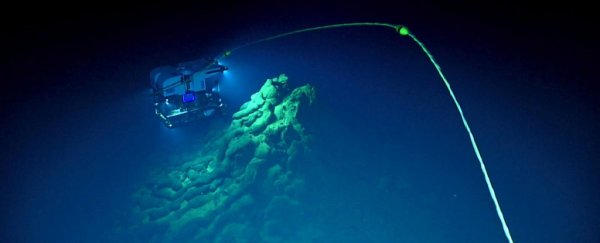

Returns to the site were made in April and December of 2016, this time with remotely-operated underwater vehicles - the NOAA's Deep Discoverer and Schmidt Ocean Institute's SuBastian - so the scientists could exert more control over what they were seeing.

Those trips showed a rapidly declining hydrothermal system, indicating that the eruption had happened on a scale of just months before the discovery in December 2015.

"Typically after an eruption, there is heat released and venting for a few years and organisms will colonise the vents, creating a new ecosystem," Chadwick explained.

"But after a while, the system cools down and the mobile organisms will leave. There was still some venting, but it had obviously greatly declined."

Images from the SuBastian dive, December 2016. (Chadwick et al./Frontiers)

Images from the SuBastian dive, December 2016. (Chadwick et al./Frontiers)

This provides a rare opportunity, since most underwater volcanic eruptions are only discovered long after they have occurred. So far, only about 40 submarine lava flows have been detected.

By returning to the site of the eruption, the researchers were able to observe the rapidity at which life moves on. By April 2016, species commonly seen living around hydrothermal vents, such as shrimp and lobsters, had started moving in; but less mobile species, such as anemones and sponges, which generally take longer to colonise, were nowhere in sight.

This, the researchers said, supported their timeline of an eruption that had only happened a short time before it was discovered.

"Undersea volcanoes can help inform us about how terrestrial volcanoes work and how they impact ocean chemistry, which can significantly affect local ecosystems," Chadwick said.

"It's a special learning opportunity when we're able to find them."

The team has published their findings in the open-access journal Frontiers in Earth Science.