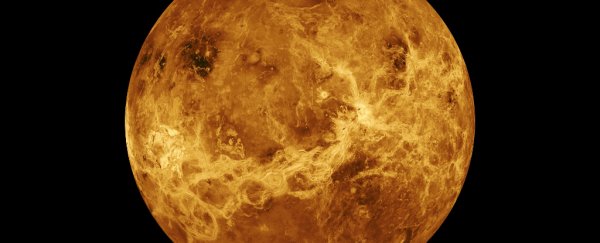

To call Venus a real oddball of a planet would be slightly understating the issue. It is so very similar to Earth – and yet at the same time as unlike Earth as one might expect an Earth-like planet to be.

One of those differences is the Venusian lithosphere – the planet's hard, outer shell. On Earth, the lithosphere is fragmented and mobile, divided up into tectonic plates that help shape the planetary surface, all the while leaking heat from the planet's interior around their jagged edges.

Venus's lithosphere, by contrast, is seamless, which makes mechanisms behind the planet's cooling and resurfacing something of a mystery.

A new study suggests that Venus may actually have a relatively 'squishy' lithosphere that's regularly resurfacing.

Studying these mechanisms is complicated and difficult: Venus is choked by a thick toxic atmosphere that rains acid and keeps surface temperatures at an average of 475 degrees Celsius (887 degrees Fahrenheit). Landers sent there have not lasted long.

But data collected by the Magellan orbiter decades ago may have been keeping Venus's secrets all these years. The spacecraft used radar to penetrate the planet's thick clouds and image the surface – and now, scientists have used that data to discover Venus's lithosphere might be be thinner than once thought.

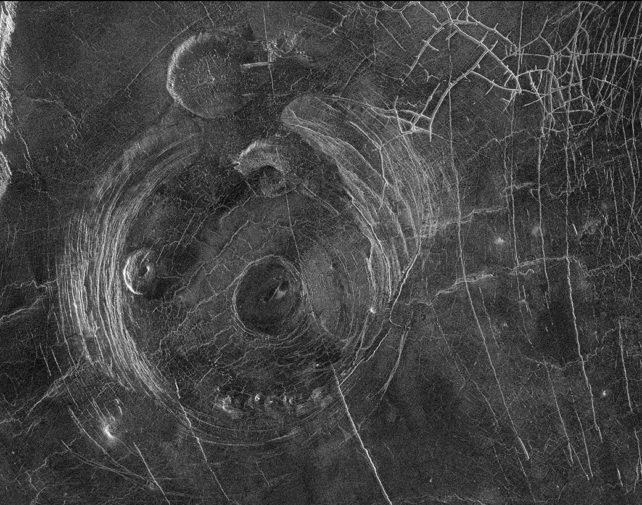

Led by planetary geophysicist Suzanne Smrekar of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a team of researchers used Magellan data to make a careful study of volcanic surface features called coronae and the trenches and ridges surrounding them. They found that, where the ridges are closer together, the lithosphere is probably quite thin and flexible, around 11 kilometers (7 miles) on average.

Modeling suggests that the heat flow through the surface is higher in these spots than the average heat flow on Earth.

"For so long we've been locked into this idea that Venus's lithosphere is stagnant and thick, but our view is now evolving," Smrekar explains.

"While Venus doesn't have Earth-style tectonics, these regions of thin lithosphere appear to be allowing significant amounts of heat to escape, similar to areas where new tectonic plates form on Earth's seafloor."

For a long time, scientists thought that Venus currently doesn't have a lot going on inside, but recent studies have been increasingly hinting otherwise. Coronae are one of those hints.

These features look a bit like impact craters, and consist of a raised ring (like a crown) around a sunken center, with concentric fractures radiating outwards. They can be huge, too, hundreds of kilometers across.

Scientists initially thought coronae were craters, but closer analysis revealed that they're actually volcanic in nature. They're caused by plumes of hot molten material welling up from the planet's interior, pushing the surface upward into a dome that then collapses inward when the plume cools, leaking from the sides to form a ring.

In truth, impact craters are relatively few and far between on Venus, at least when compared to planets like Mars and Mercury. This contrast has long been something of a puzzle. The more impact craters a planet has, the older its surface is estimated to be. If a planet has few impact craters, something must have erased them.

Venus's surface is 80 percent volcanic rock, implying some kind of mechanism for putting the planet's insides on the outside in the planet's recent past. A growing number of clues suggest that such volcanism is not just recent, but ongoing, keeping the planet's surface young.

The work of Smrekar and her colleagues supports this hypothesis. Ongoing heat loss in Venus's corona regions points to ongoing geological activity as magma roils just below the surface.

Compared to Mars, Venus has been sadly deprived of our attention in recent years, so there's a genuine dearth of up-to-date data; the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's Akatsuki probe is currently the only dedicated Venus mission. For a planet so very similar to Earth, this seems like an oversight, in spite of the challenges, but a number of agencies have Venus missions currently in development.

For NASA, that mission is VERITAS, an orbiting probe planned to launch in 2027. Scientists hope they will be able to use it to take a much closer look at Venus's curious coronae.

"VERITAS will be an orbiting geologist, able to pinpoint where these active areas are, and better resolve local variations in lithospheric thickness. We'll even be able to catch the lithosphere in the act of deforming," Smrekar says.

"We'll determine if volcanism really is making the lithosphere 'squishy' enough to lose as much heat as Earth, or if Venus has more mysteries in store."

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.