For centuries, arsenic was used as a poison of choice to discretely knock-off former lovers or political foes. It was tasteless, odourless, and it went largely undetected by the authorities - at least until the 1830s, when a chemist named James Marsh developed a forensic test to sniff it out.

While it may not be the murder weapon it once was (probably a good thing!), arsenic still poses a significant health risk to millions of people around the world who consume groundwater containing high concentrations of the element, which has a tendency to leach into aquifers from Earth's volcanic crust.

At high doses, the metal can cause vomiting, convulsions and eventually results in coma and death. Low exposures over an extended period of time, meanwhile, has been linked to liver and cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, skin lesions and cancer.

While there is no treatment for chronic exposure to arsenic, there could be a genetic clue to helping our bodies better cope with the substance.

Researchers from Sweden say they have identified a population in Argentina that has evolved a genetic mutation, which enables them to naturally break down toxic quantities of arsenic and potentially avoid some of its nasty side effects.

"They metabolise arsenic faster and to a less toxic form compared to an American or Westerner," the study's lead author, Karin Broberg, a geneticist at Karolinska Institutet, a medical university in Sweden, told NPR. "This is the first evidence of human adaptation to a toxic chemical."

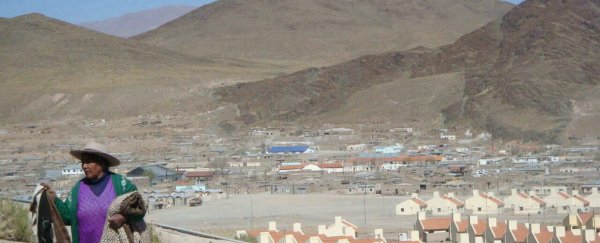

The population in question resides in San Antonio de los Cobres - a village in the far north of the country, nestled in the Andes some 4,000 metres above sea level. Importantly, it has drinking water with concentrations of arsenic 20 times greater than those recommended by the World Health Organisation.

Mummies found in the region dating back to 7,000 years ago have traces of arsenic in their hair, which led the researchers to believe this particular village had been living with arsenic-contaminated water for many successive generations. They were interested in whether this multigenerational exposure had resulted in any genetic adaptations.

The research team performed a genome wide survey on a group of 124 Andean women, and screened for the ability to metabolise arsenic - this was determined by measuring the levels in their urine. The study uncovered a key set of mutations in a gene known as AS3MT, which helps our bodies process arsenic into a less toxic form.

The researchers compared the genomes of the Argentinian women to genomes from populations in Colombia and Peru, where arsenic levels in the water are much lower. While the mutations existed in these populations, they occurred with much less frequency.

As NPR reports, "Broberg isn't sure yet how the genetic changes work. But she thinks they may increase the amount of AS3MT that's made in the liver. So more metal gets neutralised and flushed out in the urine."

And while the exact date of the selective pressure that led to the adaptation is unknown, the researchers say it probably began around the "date of settlement" between 11,000 and 7,000 years ago.

The team's results have been published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Source: NPR