Brutal violence is an undeniable part of human history. But whether our societies have become more or less violent over time is a difficult question that cuts to the heart of human nature – and one that new research takes aim at.

Some scholars maintain human violence in all its various forms, from assault and murder to slavery and torture, has declined over millennia as early societies settled into 'civilized' life.

Another camp suggests violence intensified as humans coalesced in crowded cities and inequality soared under the rule of controlling elites.

This new study of thousands of wounded skeletons from some of humanity's first cities in the Middle East presents a more nuanced view. Its findings also spell out a warning for our own times, with periods of violence occurring in cycles often tied to environmental crises.

Economic historian Joerg Baten of the University of Tübingen in Germany and colleagues examined 3,539 skeletons from the region that today covers Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Turkey. They looked for evidence of trauma, such as blows to the skull or weapon wounds on other bones, across twelve millennia.

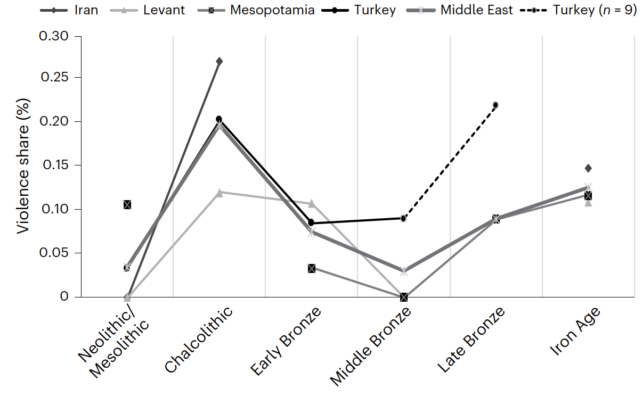

Their findings suggest human violence peaked around 5,300 to 6,500 years ago as the first cities were forming in Mesopotamia and then fell over the next 2,000 years as laws, centralized governance, and trade were established through the Early and Middle Bronze Ages (3,300–1,500 BCE).

"Although we cannot draw any causal conclusion from this synchronicity," the researchers write in a research briefing, "we can confirm that this decline in violence happened at a time when early states gained substantial capacities to reduce conflicts in their societies."

Through organized trade, cities could offer their citizens some prosperity despite declining crop yields from increasingly arid conditions, and legal systems provided a means for settling disputes.

But the lull in violence didn't last long. According to the analysis, violence rose again in the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age (1,500-400 BCE) when major crises led to the collapse of many advanced civilizations and the expansion of empires caused upheavals across the whole region.

"This was propelled by a 300-year drought, climate-induced migratory movements and general economic decay," the researchers write, drawing parallels to the Inca period in the Nasca highlands in Peru, where other studies have shown how resource scarcity due to climate shocks triggered an escalation in lethal conflict.

Similar suggestions have been made of the first horticulturalists who sought to cultivate the Atacama Desert, the world's driest desert, in what we today know as Chile. So while we can't make sweeping generalizations about human nature from such studies, trends do seem to emerge.

"There is substantial evidence that extreme climate events could impact levels of conflict," Giacomo Benati, study author and economic historian at the University of Barcelona, told Joanna Thompson for Scientific American.

"But it is also true that from our study, we see that when there are institutions that are capable of reducing and capping violence, the conflict could be reduced."

The study has been published in Nature Human Behaviour.