A virus is genetic material contained within an organic particle that invades living cells and uses their host's metabolic processes to produce a new generation of viral particles.

The way they do this varies. Some insert their genetic material into the host's DNA, where it can sit in wait until it's translated at a later date. As the host cell replicates itself, it can make new viruses.

Viruses can also burst their host cell as they expand in numbers, in what's called a lytic cycle of reproduction.

How big are viruses?

The word virus comes from a Latin word describing poisonous liquids. This is because early forms of isolating and imaging microbes couldn't capture such tiny particles.

Virus sizes vary from the extremely minuscule - 17 nanometre wide Porcine Circovirus, for example - to monsters that challenge the very definition of 'virus', such as the 2.3 micrometre Tupanvirus.

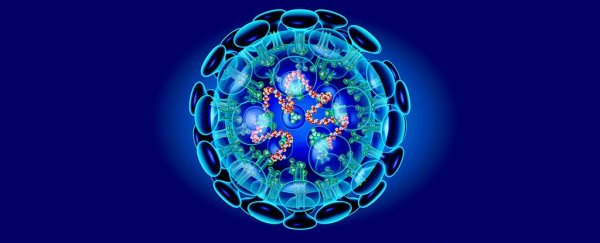

Similarly, they come in a range of complexities, containing different proteins or surrounded by an array of shells and envelopes to assist in their infection and reproduction of just about every species across every kingdom of life.

Viruses can be encoded in a variety of ways. Rotaviruses are based on a double strand of RNA, for example. Coronaviruses have a single strand of RNA, which is 'positive sense', as in it can be translated directly into new proteins. Influenza has negative sense RNA, meaning it needs an extra transcribing step before it can make proteins.

Smallpox and herpes viruses are examples of DNA viruses, which force the host to transcribe its genome into RNA on entry.

Sizes of these genomes also vary. Some of the largest can be over a million base pairs long. On the other hand, an RNA virus that infects bacteria, called MS2, has barely 3,500 base pairs.

It's impossible to know with certainty just how many types of viruses exist in the natural world, with numbers climbing as researchers use new tools to search for classified and unknown genetic signatures in the soil, oceans, and even the skies. Rough estimates suggest there could be as many as 100 million types of virus on Earth's surface.

Are viruses alive?

This is a question scientists continue to discuss as definitions of life and ecology change. Current thinking suggests viruses should be considered part of a complex living system, one that extends between all organisms.

'Virions' are the inactive particles that move through the environment, which we don't tend to think of as alive. Only once they're part of a cell do viruses take on living characteristics of their own, borrowing the host's biochemistry to reproduce.

As such, it's more accurate to think of viruses as part of the continuum between chemistry and biology, one that isn't clearly divided into living and non-living.

All topic-based articles are determined by fact checkers to be correct and relevant at the time of publishing. Text and images may be altered, removed, or added to as an editorial decision to keep information current.