We tend to associate viruses with disease and bad health, but researchers have figured out how to harness certain viruses for good, using a new technique called virotherapy to repair failing livers.

So far, the process has only been tested on lab mice, but if it can be applied to humans, the potential implications are huge - bringing damaged livers back from the brink could save thousands of lives, not to mention the huge amounts in healthcare costs. Around 35,000 people per year die of liver failure each year in the US, largely due to a lack of suitable donors.

Liver failure occurs when healthy cells called hepatocytes are damaged by alcohol or disease. They're gradually replaced with myofibroblasts, which generate scar tissue, but this can prevent new and healthy hepatocytes from being generated quickly enough.

Researchers from the University of California in San Francisco (UCSF) say the activity of myofibroblasts is kind of like patching a tyre - it works for a while, but once you've got more patch than rubber, you've got a problem.

One of the team, Holger Willenbring, was involved with previous research that led to the discovery of a 'cocktail' of reprogramming genes and chemical compounds for converting other cell types into hepatocytes. Now the team has found a way to deliver that cocktail - via an adeno-associated virus, or AAV, which can specifically infect myofibroblasts.

AAV has already been shown to be safe and effective in other gene therapy trials, which is one of the reasons the researchers chose it.

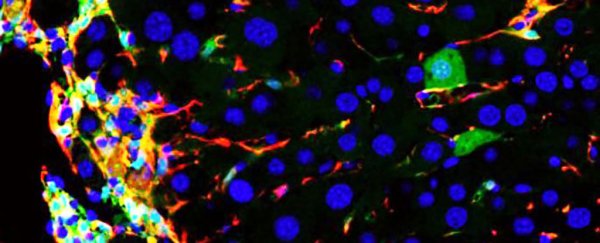

As Andy Coghlan explains for New Scientist, the key discovery of the new research is that AAVs packed with the gene cocktail did indeed convert infected myofibroblasts into functional hepatocytes. It's worth noting that the number of new cells was relatively small, but the treatment was effective enough to reduce liver damage and improve the organ's functionality.

The beauty of the new technique is that it requires no grafting of new cells, as stem cell treatment does. Instead, it uses cells that are already in place.

"Part of why this works is that the liver is a naturally regenerative organ, so it can deal with new cells very well," said Willenbring. "What we see is that the converted cells are not only functionally integrated in the liver tissue, but also divide and expand, leading to patches of new liver tissue."

While the researchers have been able to replicate the effect on human cells in a petri dish, several more years of work are required before clinical trials can start. The team wants to make the treatment even more specific to myofibroblasts and package it into a single virus, reducing the chances of any side effects.

"A liver transplant is still the best cure," says Willenbring. "This is more of a patch. But if it can boost liver function by just a couple percent, that can hopefully keep patients' liver function over that critical threshold, and that could translate to decades more of life."

The findings are published in Cell Stem Cell.