Vitamin D is important to our overall health, and now scientists have made some notable discoveries about how deficiency early in life can trigger problems with the body's immune system.

Researchers from McGill University in Canada used a combination of analysis techniques to take a close look at mice genetically engineered to not produce vitamin D naturally.

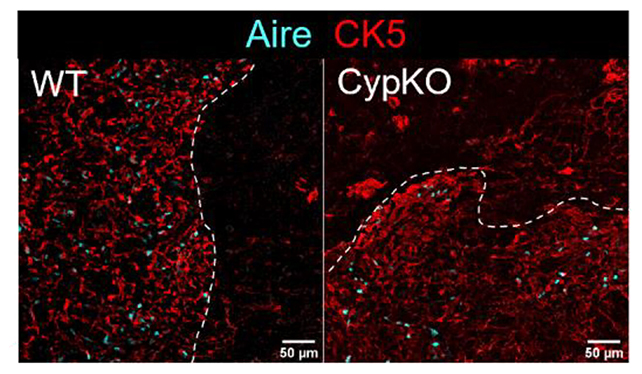

They found that the thymus – a small organ that trains our immune system – ages faster in these mice, allowing self-attacking immune cells to run rampant.

We know the thymus has an important role in educating the T cell defense force in our bodies not to attack healthy cells, and we also know vitamin D is closely linked to this process too. Now, those biological relationships are much clearer.

"Our findings bring new clarity to this connection and could lead to new strategies for preventing autoimmune diseases," says McGill University physiologist John White.

The mice unable to produce vitamin D ended up with a thymus that was smaller and contained fewer cells. There were also biological signs of premature aging in the organ, and lower levels of a key autoimmune regulator.

It shows how vitamin D deficiency can result in less protection against autoimmune diseases – where the body mistakenly attacks its own cells, leading to health complications.

"An aging thymus leads to a leaky immune system," says White. "This means the thymus becomes less effective at filtering out immune cells that could mistakenly attack healthy tissues, increasing the risk of autoimmune diseases like type 1 diabetes."

Based on earlier research, experts think vitamin D is especially crucial in kids, as the all-important T cell training in the thymus happens up until the age of 20. As we get older, the benefits of vitamin D – at least in this regard – seem less clear-cut.

That makes these findings particularly relevant to youngsters. This has only been shown in mice so far, but our thymus functions in a similar way, so there are good reasons to believe the same biological processes are at play in humans.

The researchers already have plans to investigate how vitamin D affects the human thymus (something that has not been studied before).

There's still some debate about the effectiveness of vitamin D supplements, though the general consensus is they can be beneficial if an individual is deficient – in certain areas of health.

Now we know that missing out on this crucial vitamin, perhaps through a lack of daily sunlight, really can put our immune system at a disadvantage from our earliest years.

"If you have a young child, it's important to consult with your healthcare provider to ensure they're getting enough," says White.

The research has been published in Science Advances.