It's lonely out there in deep space. Especially when a spacecraft has travelled so far into the vast emptiness, interstellar space is now all it can truly call home.

Of course, this was always Voyager 2's fate. The spacecraft – which launched over 40 years ago and now stands as NASA's longest-running space mission – was designed to venture out to the boundaries of our Solar System. For decades, it's done just that, but the incredible voyage is about to encounter a challenge it hasn't faced in all that long, lonesome journeying.

NASA has announced that Deep Space Station 43 (DSS–43) – the only antenna on Earth that can send commands to the Voyager 2 spacecraft – is going silent, and not for a short time.

The giant dish, located in Australia, and roughly the size of a 20-storey office building, requires critical upgrades, the space agency says. The Canberra facility has been in service for almost 50 years, so it's not surprising that the ageing hardware needs maintenance.

DSS–43. (CDSCC)

DSS–43. (CDSCC)

Nonetheless, the work comes at a cost. For approximately 11 months – until the end of January 2021, when the repairs are expected to be complete – Voyager 2 will be totally alone, coasting into the unknown in a quiescent mode of operation designed to conserve power and keep the probe on course until DSS–43 comes back online.

"We put the spacecraft back into a state where it will be just fine, assuming that everything goes normally with it during the time that the antenna is down," explains Voyager project manager Suzanne Dodd from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

"If things don't go normally – which is always a possibility, especially with an ageing spacecraft – then the onboard fault protection that's there can handle the situation."

During this almost year-long period of radio silence, the silence will only be one-way. Other antennas in the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (CDSCC) will be configured to receive any signals Voyager 2 broadcasts to Earth; it's just that we won't be able to say anything back, even if we need to.

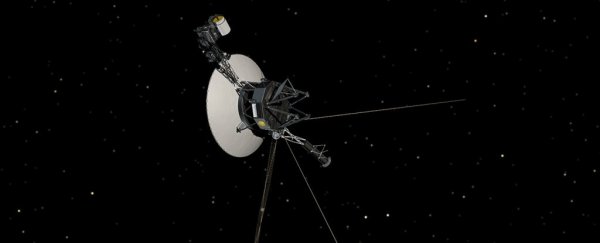

Artist's concept of Voyager 2. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Artist's concept of Voyager 2. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

While NASA has done everything it can to prepare Voyager 2 for the communications blackout, it's still a gamble – a calculated one, sure, but also seemingly an unprecedented predicament in the long duration of this historic space mission.

"There is risk in this business as there is in anything in spaceflight," CDSCC education and public outreach manager Glen Nagle told The New York Times. "It's a major change and the longest downtime for the dish in the eighteen years I've been here."

According to the space agency, the biggest unknowns are whether Voyager 2's automated thrust control systems – which fire several times a day to keep the probe's antenna oriented towards Earth – will work accurately for such an extended period, and whether power systems designed to keep Voyager 2's fuel lines sufficiently heated will also do their job.

The new challenge comes only days after NASA confirmed the spacecraft had resumed normal operations following a scare in January, when an anomaly triggered Voyager's autonomous fault protection routines.

The malfunction meant the spacecraft failed to perform a scheduled flight manoeuvre on January 25. Painstaking assessments from NASA engineers on Earth ultimately fixed the issue, with controllers having to wait 34 hours for each single response from Voyager 2, given the 17-hour transmission time for signals to travel to and from the distant probe.

Rectifying the problem involved turning five key scientific instruments off and turning them back on again – something that reportedly had never been done before – but luckily the reboot worked a charm.

Here's hoping the next 11 months proves equally successful for the far-flung Voyager 2, currently located over 17 billion kilometres (roughly 11 billion miles) from Earth, and scientifically confirmed to have now entered interstellar space, much like its twin before it, Voyager 1 (the only other human-made object to have travelled so far).

When DSS–43 upgrades are complete, the repairs will not only bolster our communications with Voyager 2 but will future-proof the facility for other upcoming missions, including future Mars missions.

Before that, though, perhaps the most pressing matter will be to reconnect ties with this famous pioneer from decades ago, as it sails ever further away, on its one-way trip to the stars.