Six years after Voyager 1 officially left the Solar System, it looks like its companion probe, Voyager 2, is getting close to the interstellar boundary as well.

According to NASA, the spacecraft has started to detect the same increase in cosmic radiation that hit Voyager 1 just before it finally entered interstellar space.

Although Voyager 2 was launched two weeks before Voyager 1 all the way back in 1977, the latter probe was on a shorter trajectory, and therefore reached Jupiter and Saturn first.

In addition, while Voyager 2 received a gravity assist from Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus, its Neptune flyby slowed it down, so it lagged behind even farther.

As both probes continued their epic journey, on 25 August 2012 Voyager 1 officially crossed the border between our Solar System and the space beyond, becoming the first human-made object to head out into interstellar space.

Now Voyager 2, true to its name, is poised to finally become the second.

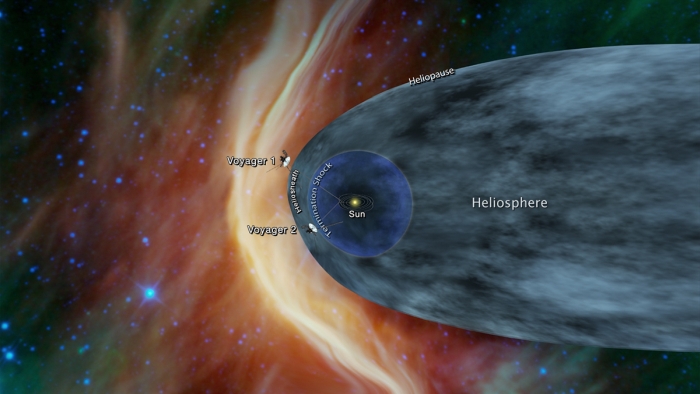

The pressure in space is extraordinarily low, but it still exists. Throughout the Solar System, the wind from the Sun exerts an outward pressure. At a certain point, that wind is no longer strong enough to push back against interstellar space.

That point, located on average around 123 astronomical units (AU; 18.4 billion kilometres, or 11.4 billion miles) from the Sun, is called the heliopause.

On one side is the heliosphere, the Solar System's bubble carved out by the solar wind. On the other side is the rest of the freaking Universe.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Voyager 2 has been travelling through the outer heliosphere since 2007, when it crossed the termination shock - the point at which the solar wind slows down to below the speed of sound. The probe is currently about 118 AU (17.7 billion kilometres, or 10.9 billion miles) from the Sun.

"Since late August, the Cosmic Ray Subsystem instrument on Voyager 2 has measured about a five percent increase in the rate of cosmic rays hitting the spacecraft compared to early August," NASA wrote in an announcement.

"The probe's Low-Energy Charged Particle instrument has detected a similar increase in higher-energy cosmic rays."

Cosmic rays are subatomic particles, primarily hydrogen and helium nuclei, that zoom through space at incredibly high speeds. It's thought that many of these get stopped or slowed at the heliopause by the solar wind, creating a sort of cosmic ray build-up between the heliopause and the termination shock.

In May 2012, about three months before it crossed the heliopause, Voyager 1 saw a similar increase in cosmic rays. But the similarity between the two probes' experiences doesn't mean that Voyager 2 is about to cross over.

This is because the Solar System slightly expands and contracts during the 11-year solar cycle.

When the Sun is at minimum - which we're currently closing in on - its activity levels are low, and the Solar wind is slower. At maximum, the solar wind is significantly stronger.

So while we can guess at a few things, there are still some surprises ahead, which means the Voyager team will be keeping a close eye on things. So far, the only prediction that can be made with a degree of certainty is that it will enter interstellar space before 2030.

"We're seeing a change in the environment around Voyager 2, there's no doubt about that," said Voyager Project Scientist Ed Stone of Caltech.

"We're going to learn a lot in the coming months, but we still don't know when we'll reach the heliopause. We're not there yet - that's one thing I can say with confidence."

We believe in you, little space probe!