Several months ago, doctors at the Countess of Chester Hospital in England arrived at a rather unusual diagnosis for the blisters on a 15 year old adolescent's hands and feet – cowpox.

There hasn't been a case like it in the entire country for more than a decade, but just a couple of centuries ago it would have been a far more common disease. In fact, it once played a key role in one of the most important discoveries in medical history.

The word vaccination comes from the Latin word for cow – vaccinus – thanks to its origins among the milk maids of rural England.

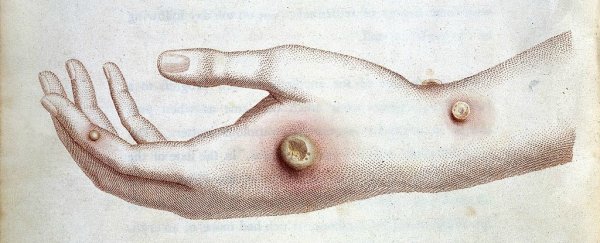

As the short version of the famous story goes, physician Edward Jenner took inspiration from earlier discoveries and practices on acquired immunity to scrape pus from the cowpox blisters commonly found on the hands and arms of milk maids, only to then jab it into the skin of other people.

He figured that whatever caused cowpox, it seemed to make the milk maids less susceptible to a far more deadly disease: smallpox.

Unlike smallpox, cowpox isn't easily passed from human to human. So to share the secret weapon, Jenner was forced to go for the more aggressive 'pus poking' option.

Vaccination no longer relies on the transfer of cowpox, and a recent discovery suggests it possibly never did. In any case, the disease continues to have a starring role in this celebrated part of medical history.

Not that this young chap from Wales seemed impressed by the history of his condition. Understandably, he's chosen to remain anonymous.

"My son was quite embarrassed," the teen's mother told the BBC.

"It looked quite a mess, they (the lesions) weren't nice and it wasn't pleasant for him."

They took a few weeks to clear up, and while they pustules weren't painful they were claimed to be rather itchy.

It appears that the patient picked up the infection while feeding some calves, which ironically was an even greater misfortune than it would first appear.

In contrast to its name, it's far more likely to pick up the virus from feral cats and rodents than cows, which aren't particularly susceptible to the virus.

As unusual as it all is, it doesn't necessarily spell out a resurgence. Not yet at least.

"A total of 29 laboratory reports of cowpox were received by the public health laboratories (PHLS) communicable disease surveillance centre between 1975 and 1992 (with a range of 0 to four reports annually)," clinical scientist Robert Smith from Public Health Wales told the BBC.

But it is unusual enough to appear on the radar of epidemiologists, just in case.