We humans may be the most advanced species in the animal kingdom, but there are some things that we're definitely hopeless at: such as seeing in the dark.

Why do creatures such as owls and cats have night vision that's so much better than ours? It's a question that biologist Anna Stöckl, from Lund University in Sweden, tackles in a new TED-Ed video, which you can view above.

Interestingly, different animals have evolved to use different methods for seeing in the dark. But before we get into that, it's helpful to know how our own eyes work in low light.

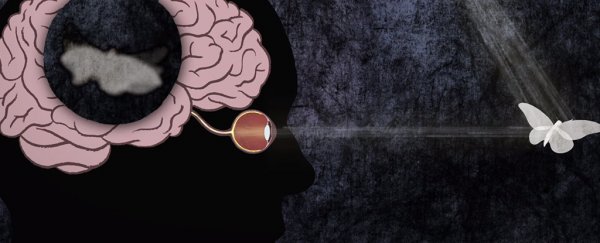

Our eyes are essentially capturing light particles called photons, which hit photoreceptors in the retina at the back of the eye. They're converted into electrical signals and sent back to the brain, which interprets them and works out what we're seeing.

The more light there is in the world around us, the more photons arrive at the eye, and the better we can see. When it's bright, they also hit the eye in a more reliable and uniform way – which is why everything gets fuzzy at night-time.

While our eyes do make some adjustments when it goes dark – like the pupil expanding to let in more light – we're still not as good at seeing in darkness as many other creatures.

Take tarsiers, which have eyes as big as their brains to let in as much light as possible – in fact, they actually have the biggest eyes proportionally when compared to the head sizes of all other mammals.

It may cost them something in the cuteness stakes, but at least these bug-eyed creatures can still see what's happening when the Sun goes down.

Owls have very large eyes too – also allowing them to collect more photons – in addition to specialised rod cells at the back of the eye. Rounding out the package, a reflector system in owl eyes called tapetum lucidum lets them see the arriving light not once but twice.

Then there are cats, which also benefit from the same tapetum lucidum structure. To someone watching, it gives cat eyes an eerie glow as light bounces back out through the photoreceptors – and of course a similar reflection system is used in the cat's eyes safety devices embedded in our roads.

Toads, meanwhile, use a different technique: their eyes take their time to build up an image, to allow as many photons as possible to arrive. It means they only get an updated view of the world every four seconds, but that's usually enough to catch whatever slow-moving prey is on the menu.

Then we have hawkmoths, which can actually see flowers in colour in the dead of night. They do this by grouping information from neighbouring photoreceptors together – which means some detail and sharpness is lost – but it still lets the insects work out which flowers they should be heading for.

All in all, it's pretty amazing what animal eyes can do. But at least there's one thing we humans have that they don't: light switches.