Why is it that some people are able to pick up a guitar and just know how to play a new song on it, or can hear an 'A' note and identify it immediately, while the rest of us can barely play Mary Had A Little Lamb on the piano? Is music something you learn, or are some people born to be more in tune (sorry) with it?

In the latest episode of SciShow, Hank Green discusses a new paper published in the Royal Society B, which looked at all research published over the past decade on the question: 'Musical ability: learned or genetic?'. Their conclusion? Genetic.

The collection of studies found that musical phenotypes - observable traits carried by your DNA - corresponded significantly with familial clustering, which means it occurs in more members of a family than would be expected by chance. So if your whole family is musical inept, you're more likely to be similarly inept, or if your family consists of a bunch of musical geniuses, well, congratulations, you're more likely to be one too.

The team looked at a few aspects of 'musicality', or the absence of musicality, such as tone-deafness - also known as amusia - where a person is incapable of identifying which notes are out of key, and perfect pitch, where a person can identify or re-create a given musical note just by hearing it. And with no other notes to compare it to.

"In 2007, scientists tested the family members of nine people who had amusia, and found that 39 percent of their first-degree relatives - brothers, sisters, mum, and dad - also had the condition," says Hank.

And when it comes to perfect pitch, when scientists compared the presence of this very rare ability in identical twins, they found that if one had it, there was a 79 percent chance their sibling had it too. This percentage decreases to 45 percent in non-identical twins.

Sure, this could all come down to the environments that twins, or family members are growing up in, which is why scientists are now looking for more evidence in the DNA. And they've now begun identifying sections in the human genome that may be directly linked to musical ability, says Hank in the episode of SciShow above.

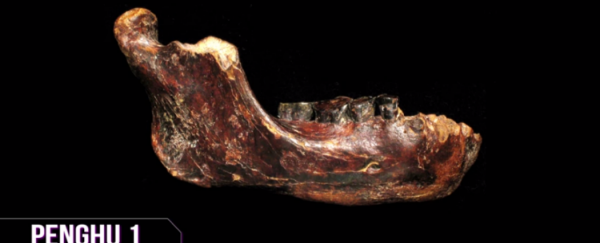

Speaking of genes, we know that the primitive relatives of the modern human - or Homo sapien - include the Neanderthal, Homo erectus, and Homo floresiensis, but recent research suggests that there might have actually been another one. The discovery of a fossilised lower jaw bone in Taiwan has led scientists to suggest that an entirely new species of human also existed, as recently as 10,000 years ago.

"The newly discovered big-toothed human, 'Penghu 1', strengthens the growing body of evidence that Homo sapiens was not the only species from our genus living in Europe and Asia between 200,000 and 10,000 years ago," Jennifer Viegas reported for Discovery News last month.

Penghu 1 appears to have had bigger teeth and a more robust jaw than Homo erectus did around the same time, says Hank, and it also would have looked different from the 14 other types of hominids that existed 20,000 to 10,000 years ago. So what does this mean for our ancient family tree? Watch the latest episode of SciShow above to find out.

Source: SciShow