Life's most vital elixir may have formed within 200 million years of the Big Bang, new research suggests. Conditions for producing water were thought to be lacking this early on because heavier elements like oxygen were scarce, but new simulations indicate the baby Universe could still have been wet.

Cosmologist Daniel Whalen from Portsmouth University in the UK and colleagues virtually recreated the explosions of two stars using early Universe parameters, and found the means to make water were already present as early as 100 million years after the Universe exploded into existence.

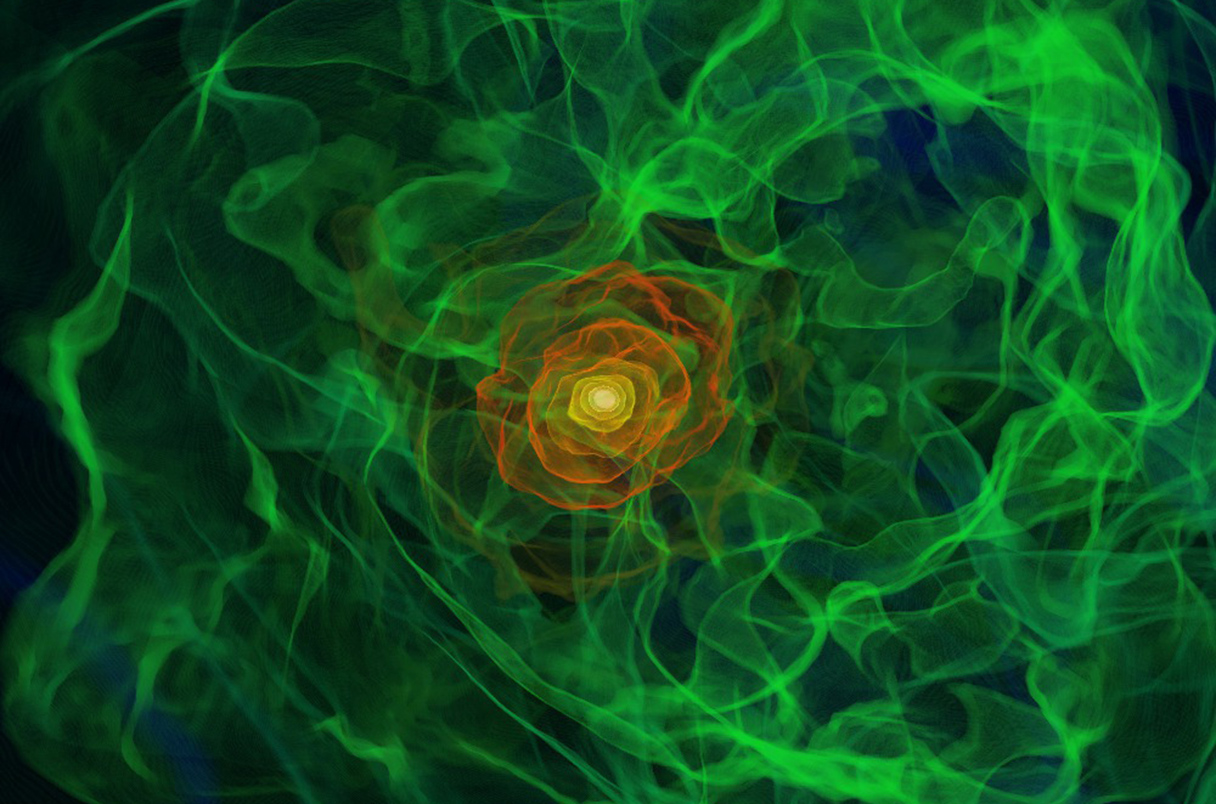

The video below illustrates gases of hydrogen, helium, and lithium from the Big Bang coalescing into the first stars, releasing heavier elements like oxygen into the Universe during their explosive deaths:

"Our simulations suggest that water was present in primordial galaxies because of its earlier formation in their constituent haloes," the researchers write in their paper.

Today, highly metallic stars have an abundance of oxygen in their cores, but the first stars were made almost entirely out of hydrogen and helium. These early stars likely burnt hot and fast, making it hard for astronomers to catch traces of them, but new data from JWST may have just revealed the first direct evidence of their existence.

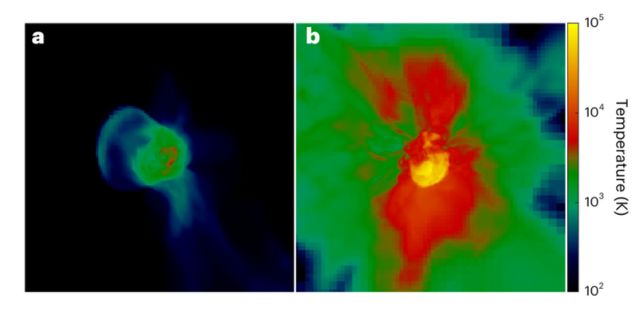

Whalen and team simulated the explosion of these early stars, one that was 13 times and another 200 times the mass of our Sun.

Within the first second of the virtual supernovae, the temperatures and pressures were high enough to fuse more of the former star gases into oxygen. In the aftermath of this cataclysm, the expelled energized gases, stretching out as far as 1,630 light-years, began to cool.

The rapid cooling happened faster than the material coalesced, causing ionized hydrogen molecules to pair up, forming water's other key ingredient: molecular hydrogen (H2).

As these particles jostled about, particularly in the denser regions of the supernova haloes, oxygen collided with enough hydrogen to make the Universe wet.

What's more, these denser clumps of supernova leftovers, with their higher concentrations of metals, likely also become the sites of the next generation of heavier element-filled stars and future planet formation, the researchers suspect.

"The higher metal content… could, in principle, lead to the formation of rocky planetesimals in protoplanetary disks with low-mass stars," Whalen and team say.

This means the potential planets could also harbor water.

Several stars may also form together in the same region, the researchers explain.

"If so, several supernova explosions may occur and overlap in the halo," Whalen and colleagues explain. "Several explosions may produce more dense cores and, thus, more sites for water formation and concentration in the halo."

In areas where the halo gas is sparse, multiple explosions would destroy the formed water, but in the denser cloud cores, H2O has a higher chance of surviving, thanks to dust shielding it from radiation.

The team's calculations suggest the amount of water produced by the earliest galaxies may have been only ten times less than what we see in our galaxy today, suggesting one of life's major ingredients was amply abundant very long ago.

This research was published in Nature Astronomy.