The scientific community is in danger of overstepping (or may have already breached) its ethical responsibilities in a rush to study and understand the mysteries of the brain via experimentation with artificially grown substitutes, researchers warn.

Mini-brains, also known as organoids, have in recent years become a hugely important resource in neuroscience and related fields.

But while these lab-grown analogues grown from stem cells aren't technically considered human or animal organs, they're becoming functionally close enough to warrant serious ethical concerns – if not an outright ban on their use, according to some neuroscientists.

In a presentation this week at the world's largest gathering of neuroscientists, a team led by researchers from the Green Neuroscience Laboratory in San Diego made the case for why there is an "urgent need" for scientists to develop a framework of criteria that stipulates what 'sentience' is, so that future research using mini-brains and stem cell cultures can be bound by a developed set of ethical rules.

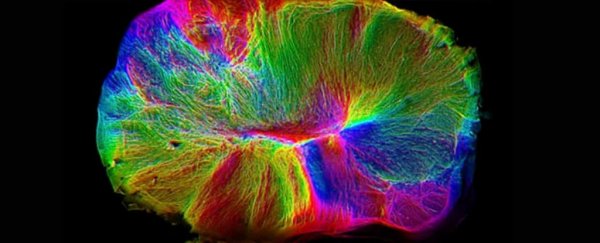

Mini brains at 10 months. (Muotri Lab/UCTV)

Mini brains at 10 months. (Muotri Lab/UCTV)

"The compositional and causal features in these cultures are – by design – often very similar to naturally occurring neural substrates," the team explains in their abstract.

"Recent developments in organoid research also entail that the anatomical substrates are now approaching local network organisation and larger structures found in sentient animals."

There's a lot of evidence to support this. In recent years, scientists have promoted mini-brains as an economical and practical alternative to animal testing, and advancements in nurturing stem cells are helping scientists figure out how to mimic the complex neural subtypes of human brain tissue.

Mini-brains grown in dishes have enabled researchers to probe the differences between humans and chimpanzees, and the rapid pace with which the field is evolving is almost scary.

In March, scientists grew a mini-brain – said to be roughly analogous in complexity to a human foetal brain at 12 to 13 weeks – and, in the context of their model experiment, it spontaneously connected itself to a nearby spinal cord and muscle tissue.

A few months later, in a separate experiment, researchers detected electrical activity exhibited by organoids that looked startlingly similar to human brain waves.

While the scientific teams behind these incredible accomplishments are usually quick to observe that the organoids we're capable of developing today are far removed from showing the neural sophistication of human and animal brains, Ohayon and his team's computational models suggest we're getting awfully close to growing sentient brains in a dish.

"Current organoid research is perilously close to crossing this ethical Rubicon and may have already done so," the researchers explain.

"Despite the field's perception that the complexity and diversity of cellular elements in vivo remains unmatched by today's organoids, current cultures are already isomorphic to sentient brain structure and activity in critical domains and so may be capable of supporting sentient activity and behaviour."

The Green Neuroscience Laboratory is run by Elan Ohayon and Ann Lam, two neuroscientists who have outlined a "Roadmap to a New Neuroscience": a set of core ethical principles for their research, designed to exclude "toxic methodologies", animal experimentation, and methods that otherwise infringe an individual's rights, privacy, and autonomy.

From their viewpoint, the state of sophistication in current mini-brain research means we should be affording the same kinds of protections to primitive organoids that might be just complex enough to have thoughts and sensations.

"If there's even a possibility of the organoid being sentient, we could be crossing that line," Ohayon told The Guardian.

"We don't want people doing research where there is potential for something to suffer."

The Green team aren't the only scientists with such qualms. In a study published this month, neuroscientists from the University of Pennsylvania argued why the field needs guidelines that don't currently exist – especially in the context of experiments where lab-grown organoids are transplanted into animal host bodies.

"The field is developing quickly, and as we continue down this path, researchers need to contribute to the creation of ethical guidelines grounded in scientific principles that define how to approach their use before and after transplantation in animals," says neurosurgeon Isaac Chen.

"While today's brain organoids and brain organoid hosts do not come close to reaching any level of self-awareness, there is wisdom in understanding the relevant ethical considerations in order to avoid potential pitfalls that may arise as this technology advances."

The research was presented at Neuroscience 2019, the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, held in Chicago this week.