The mystery of dark matter could be solved in as little as 10 seconds.

When the next nearby supernova goes off, any gamma-ray telescope pointing in the right direction might be treated to more than a light show – it could quickly confirm the existence of one of the most promising dark matter candidates.

Astrophysicists at the University of California, Berkeley predict that within the first 10 seconds of a supernova, enough hypothetical particles called axions could be emitted to prove they exist in a relative blink.

Given the years it might take to chance upon a convincing number through other means, catching an axion windfall in a close-by star collapse would be like winning the physics lottery.

Of course, that detection requires that we have a gamma-ray telescope looking in the vicinity of such an explosion at just the right time. Currently that job falls solely on the Fermi Space Telescope, which still only has a 1 in 10 chance of catching the show.

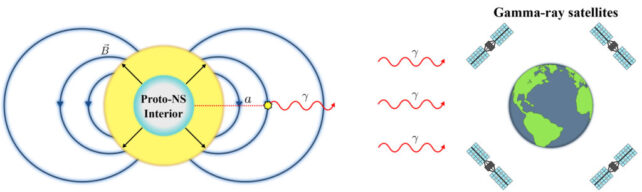

So, the researchers propose launching the GALactic AXion Instrument for Supernova (GALAXIS) – a fleet of gamma-ray satellites that can watch 100 percent of the sky at all times. The detection or absence of axions during a supernova could be equally valuable outcomes, but there's a time crunch.

"I think all of us on this paper are stressed about there being a next supernova before we have the right instrumentation," says Benjamin Safdi, associate professor of physics at UC Berkeley.

"It would be a real shame if a supernova went off tomorrow and we missed an opportunity to detect the axion – it might not come back for another 50 years."

Axions were first hypothesized in the 1970s as a potential solution to a physics puzzle unrelated to dark matter, the strong CP problem. These particles are predicted to have a very tiny mass, no electric charge, and be extremely abundant across the Universe.

It was only later that other physicists realized some of their properties – such as the way they clump together, and mostly interact with other matter through gravity – made them a good candidate for dark matter. Most importantly, one predicted property could make them detectable.

In strong magnetic fields, axions should occasionally decay into photons, so detecting extra light near these fields could give them away. This has been the basis of lab experiments and astronomical observations for decades, allowing scientists to whittle down the range of masses axions might have.

Neutron stars are among the most promising places to look for them. Their intense physics should produce huge amounts of axions, and even better, the strong magnetic fields should convert some of them into detectable photons.

In the new paper, the UC Berkeley team calculates that the best time to find axions around a neutron star might actually be at its birth – when a massive star explodes as a supernova. New simulations suggest that a burst of axions would be produced during the first 10 seconds after the star's collapse, and the resulting gamma-ray burst could reveal a lot of detail.

The team calculated that a particular type of axion, called a quantum chromodynamics (QCD) axion, would be detectable through this method if it has a mass higher than 50 micro-electronvolts, which is just one 10-billionth the mass of an electron.

If axions do turn out to exist, they could be one of the handiest little particles ever found. In one fell swoop they could help us unlock dark matter, the strong CP problem, string theory, and the matter/antimatter imbalance.

The hypothesis is ready for testing – now we just have to wait until the next nearby supernova. It could happen today, or in another decade's time, and if Fermi is watching the right patch of sky we could answer some of science's most profound questions within seconds.

"The best-case scenario for axions is Fermi catches a supernova," says Safdi.

"The chance of that is small. But if Fermi saw it, we'd be able to measure its mass. We'd be able to measure its interaction strength. We'd be able to determine everything we need to know about the axion, and we'd be incredibly confident in the signal because there's no ordinary matter which could create such an event."

The research was published in the journal Physical Review Letters.