Scientists have found a bunch of microscopic creatures that could be totally new to science - but it's an exceptional challenge to determine who is who when the tiny things you've discovered are actually the larva of animals that look completely different in their adult stage.

The little-known animals in question are called phoronids, or horseshoe worms. The adults anchor themselves in sediment or to rocks or coral, building a tube of chitin to protect their soft bodies, while their heads are crowned with tentacles that wave in the current to strain small particles of food from the water for filter-feeding.

The don't live very deep - from the intertidal zone to around the top of the mesopelagic zone, 400 metres (1,320 ft) or so - and they can be found in most of the world's oceans. Most of the adults range from around 2 centimetres up to about 20 centimetres in length.

So, fully grown, they're not hard to find - the first phoronid was described in 1856.

But matching them up to their young? That's a little harder. The first phoronid larvae were actually described before the adults, in 1846 - but they look so different they were put into a completely different genus, Actinotrocha. That's why today, they're called Actinotrochs.

The categorisation has since been overhauled, but there's still a lot of work to be done figuring out which baby goes with which parents - and how many species there may actually be.

"The global diversity of small, rare marine animals like phoronids is grossly underestimated," said marine biologist Rachel Collin of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. "We don't know what animals are out there, and we know even less about what their role might be in the world's oceans."

So, to try and shed more light on the matter, Collin and her team collected a whole bunch of phoronid larvae.

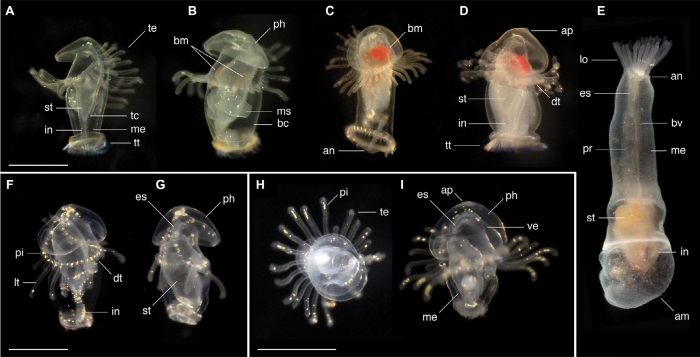

Now, these little guys don't look much like their adult parents. They are free-floating, microscopic, with a ring of tentacles capped by a domed hood. Some have yellow spots; others are so clear that their internal fluids are visible.

Eventually they'll sink and anchor themselves and grow into the worms that wave their fronds in the current. But which worms? The most reliable method of finding out is by comparing their DNA with that of adult phoronids, so this is what the team set out to do.

They collected 23 phoronid larvae from the Bay of Panama on the Pacific coast, and 29 from Bocas del Toro on the Caribbean coast, sequenced their DNA, and compared it to the adult phoronid information stored in DNA database GenBank.

Actinotrochs collected from the Bay of Panama. (Michael Boyle)

Actinotrochs collected from the Bay of Panama. (Michael Boyle)

They were able to distinguish three distinct phoronids from the Bay of Panama, and four from Bocas del Toro. These seven had DNA different from anything in GenBank, which contains the DNA of 75 percent of recognised adult phoronid species.

DNA sequencing for one larva failed, which means that it, too, could potentially be an unknown species - bringing the total of potential new species collected by the team to eight.

But there aren't a lot of scientists looking for or studying phoronids, so 'unknown' is the way these creatures could remain, the researchers noted.

"Because of the cryptic lifestyles of phoronids, the matching adult worms may never be found," said biologist Michael Boyle of the Smithsonian Marine Station, "yet the presence of their larval forms in plankton confirm that they are here, established and reproducing."

To be honest, though, there is something comforting about the thought of unknown creatures living their secretive lives, unconcerned about the goings-on of bipedal primates on the surface far above.

It's a beautiful world we live in, and we hope it will always continue to surprise us.

The research has been published in Invertebrate Biology.