Researchers have finally found credible records of someone being killed by a falling meteorite.

On 22 August 1888, according to multiple documents found in the General Directorate of State Archives of the Presidency of the Republic of Turkey, a falling meteorite hit and killed one man and paralysed another in what is now Sulaymaniyah in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq.

This constitutes, according to researchers, the first-ever known proof of death by meteorite strike. And it hints there could be more such records out there, hiding in archives, waiting to be discovered.

Earth is not an unassailable fortress. It's under a constant bombardment of space rocks; it's estimated that millions of meteors per day hit the atmosphere. To be fair, not many of them survive atmospheric entry.

But, according to NASA's fireball database, at least 822 have been big enough to explode in the atmosphere since 1988, raining down meteorite debris. And some scientists believe that up to 17 meteors could hit Earth's surface every day.

You'd therefore think that someone, somewhere would have been hit and killed by a falling chunk of space debris over the years, but historical records have been strangely bereft of reliable reports of this occurring.

Even the massive Chelyabinsk meteorite in 2013, which exploded in the atmosphere and rained down chunks weighing up to 654 kilograms (1,442 pounds), didn't kill anyone; all injuries reported were from the effects of the shockwave, not falling meteorite.

According to a 1951 paper published in Popular Astronomy, the difficulty to provide historical evidence "arises not from any dearth of apparently relevant incidents but chiefly from the lack of material evidence that the missiles involved in the accidents were genuinely meteoric and the impossibility of subjecting to critical questioning either survivors or eyewitnesses of the sensational events described."

A man tragically killed in an explosion in India in 2016 was widely reported to be the first such death - but, according to NASA experts, that explosion was not caused by anything extraterrestrial.

So, to the best of our knowledge, death by meteorite is vanishingly rare; the only confirmed victim of a meteorite strike is a woman named Ann Hodges, who was napping on her couch in 1954 when the rock fell through her roof and hit her hip. The rock was retrieved, and confirmed to be extraterrestrial in origin. Hodges survived.

Although there is no rock to verify the 1888 report - apparently there was one, but the researchers couldn't find it - the archival documents are extremely convincing.

The researchers found three separate documents describing the incident. They had only been recently transferred to a digital archive, and were penned in a difficult-to-translate Ottoman Turkish language, which explains why they hadn't been uncovered before.

The documents are letters written by local authorities reporting the incident to the government. On August 10 of the Julian calendar (August 22 on the Gregorian calendar), the letters report, at about 8:30 pm in the evening local time, a large fireball was seen in the sky.

After this event, meteorites fell "like rain" from the sky for a period of about 10 minutes on a small village, resulting in the death of one unnamed man, and the paralytic injury of another. In addition, damage to crops was reported - which is consistent with a fireball shockwave.

(Unsalan et al., Meteoritics and Planetary Science, 2020)

(Unsalan et al., Meteoritics and Planetary Science, 2020)

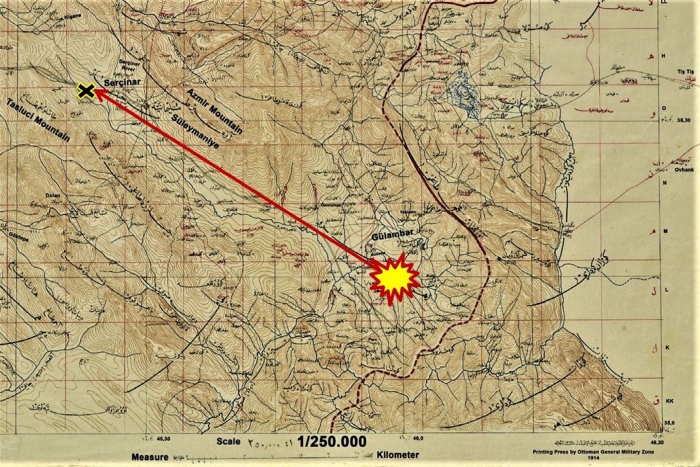

It's impossible to know the exact altitude, speed, size and location of the fireball. But, based on the villages where it was seen, the researchers believe the meteorite travelled from the southeast before its pieces impacted on a pyramid-shaped hill in Sulaymaniyah.

"This event is the first report ever that states a meteor impact killed a man [..] with the support of three written manuscripts that report an event in such detail up to our knowledge," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"Due to the fact that these documents are from official government sources and written by the local authorities, even grand vizier himself as well, we do not have any suspicion on their reality."

The team is still combing the archives, and will be looking for more information on this event. They believe that a reply from the Sultan may be in documents that are yet to be digitised and organised, and there are documents already in the digital archives that have not been examined.

But the find is an interesting one, because it points to a large gap in our knowledge, the researchers point out. It's not just that the historical record is vast, and could be under-studied; there is also a lack of work on historical documents in languages other than English.

"In order to overcome such difficulty, a great deal of work and interdisciplinary collaborations with historians, librarians, and translators is an obligation," the researchers wrote.

The research has been published in Meteoritics & Planetary Science.