Millions of years ago, an epic journey began from Mars. A giant asteroid slammed into the surface, gouging out chunks of the Martian crust and hurling them into space.

In 2011, one of those chunks of rock was fished out of the Sahara Desert. Its trajectory had carried it, by chance, all the way to Earth (that, or Mars deliberately started throwing rocks at us).

Nicknamed Black Beauty for its glorious dark glossy hue, the meteorite catalogued NWA 7034 is thought to be the oldest chunk of Mars we have. And now it has been traced to the precise location where the asteroid that launched it struck.

The team has named that impact crater Karratha, after a region in Australia where some of Earth's oldest rocks can be found. This new geological context for the rock – a volcanic mineral, composed of different kinds of rock (a bit like a fruit cake) in what's known as a breccia – will aid comparisons of the formation history of Earth and Mars.

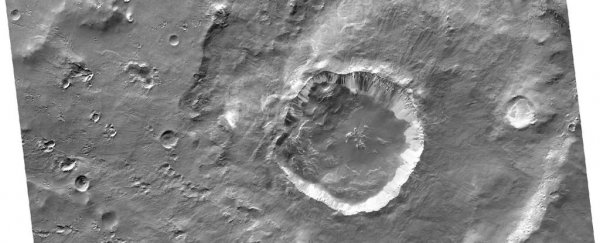

Karratha Crater inside Dampier Crater. (NASA MRO)

Karratha Crater inside Dampier Crater. (NASA MRO)

"For the first time, we know the geological context of the only brecciated Martian sample available on Earth," explained planetary scientist Anthony Lagain of Curtin University in Australia, who led the international team of researchers.

"Finding the region where the 'Black Beauty' meteorite originates is critical because it contains the oldest Martian fragments ever found, aged at 4.48 billion years old, and it shows similarities between Mars' very old crust, aged about 4.53 billion years old, and today's Earth continents. The region we identify as being the source of this unique Martian meteorite sample constitutes a true window into the earliest environment of the planets, including the Earth, which our planet lost because of plate tectonics and erosion."

To date, around 300 meteorites from Mars have ended up here on Earth (maybe Mars has a grudge). Black Beauty, consisting of a 320-gram (11-ounce) chunk of rock and a pair of stones, is absolutely one of a kind: In addition to being the oldest piece of Mars we have, it's the only piece of volcanic breccia among all of them.

Black Beauty. (NASA)

Black Beauty. (NASA)

It's thought to be a record of early conditions on Mars – but where on Mars had remained a mystery. The red planet is positively riddled with impact craters, making tracing a meteorite to any one of them extremely challenging.

To do so, Lagain and his colleagues used the powerful Pawsey Supercomputing Research Centre in Western Australia, and an algorithm developed at Curtin University for the express purpose of detecting impact craters. An analysis of the size and spatial distribution of 90 million craters detected by this algorithm allowed scientists to narrow down the origin of Black Beauty.

Their results revealed multiple impacts went into forming Black Beauty. The oldest fragments of the rock were blasted from the Martian crust around 1.5 billion years ago from a spot marked by the 40-kilometer-across (25 miles) Khujirt crater in the southern hemisphere of Mars. This material fell back to Mars, where it remained until around 5 to 10 million years ago, when the impact that created the Karratha crater threw it up again, sending it flying into space on its journey to Earth.

Khujirt Crater, imaged by the Viking orbiter. Dampier and Karratha can be seen in the top right. (NASA)

Khujirt Crater, imaged by the Viking orbiter. Dampier and Karratha can be seen in the top right. (NASA)

Previous research at Curtin found shocks in the meteorite's zircon crystals dating back to 4.45 billion years ago, indicative of a massive impact then, too. Although the site of that putative impact remains unknown, it seems that some of the material in Black Beauty may have been involved in at least three impacts on Mars.

The findings suggest that the region from which the rock was initially ejected may be a relic of the primordial Martian crust, and therefore of intense interest for future Mars exploration.

The work, in addition, could be used to trace the origins of some of the other meteorites that Mars has chucked at Earth. This could help reconstruct in greater detail a timeline of Mars' geological history. And there are implications for other heavily cratered bodies in the Solar System too, such as Mercury and the Moon.

"We are … adapting the algorithm that was used to pinpoint Black Beauty's point of ejection from Mars to unlock other secrets from the Moon and Mercury," said astro-geologist Gretchen Benedix of Curtin University.

"This will help to unravel their geological history and answer burning questions that will help future investigations of the Solar System such as the Artemis program to send humans on the Moon by the end of the decade or the BepiColombo mission, in orbit around Mercury in 2025."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.