From shifting skink rainbows to dazzling hummingbird metallics, many creatures display brilliant hues created by nano-structures weaving wavelengths of light.

Researchers led by Utrecht University bioinformatician Aldert Zomer have now pinpointed genes that allow bacteria to make use of this vivid phenomenon too.

Where colors emitted by pigments are the leftover parts of the visible light spectrum that aren't absorbed, structural colors arise from the way light interferes as it is reflected.

The projected colors depend on how small-scale structures on the surface of a material direct light, causing some wavelengths to combine or cancel. What a viewer sees can shift according to their viewing angle, causing dramatic changes in color intensity or iridescent color transitions.

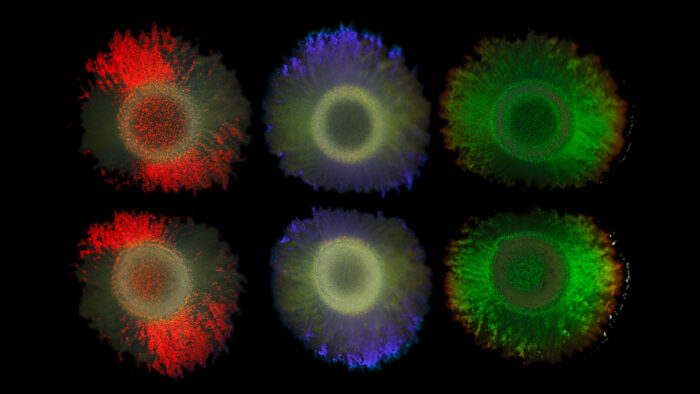

Individual microbes, such as the marine bacterium Marinobacter alginolytica, can act as nanostructures, coordinating with each other to form colonies in a precise pattern that allows them to reflect specific wavelengths.

"Bacterial colonies with structural color are living nanostructures that manipulate light, and we have identified several molecular pathways that are linked to the process of generating them," Zomer and team write in their paper.

The researchers compared the genomes of 87 strains of bacteria that can form structurally colored colonies with 30 colorless strains to find the genetic fingerprint of this phenomenon. With the help of AI models the team then explored 250,000 bacterial genomes and 14,000 environmental samples to see what other bacteria possessed structural color.

Surprisingly, structural color even appeared in bacteria that live where there's no light to reflect.

"We discovered that the genes responsible for structural color are mainly found in oceans, freshwater, and special habitats such as intertidal zones and deep-sea areas," explains University of Jena viral ecologist Bas Dutilh. "In contrast, microbes in host-associated habitats such as the human microbiome displayed very limited structural color."

That structural color appears in the ocean's depths suggests the nanostructures involved likely serve biological processes other than dazzling observers. For example, they may act as defensive structures against viruses or help the cells latch onto floating food particles, the researchers explain.

Or structural color in bacteria may even have arisen merely as a side effect of how bacteria organize themselves into their colonies.

Understanding how nature creates structural colors could allow us to develop environmentally friendly materials with enduring colors and other desirable properties like light weight paint for planes.

This research was published in PNAS.