Like the crooked finger of a fairy-tale witch, a fragmented ivory artifact recovered from an Ice Age dig site in southwest Germany several years ago almost wills to be pointed with sorcerous intent.

Similar items have been discovered across the continent over the past century, all inviting speculation over the objects' purposes. Whittled into points, perforated with holes, thoughts have turned to wands and scepters. Or perhaps of flutes, or symbols of occult power. Instruments of ritual and magic.

Nicholas Conard, an archeologist from the University of Tübingen in Germany, and fellow archeologist Veerle Rots from the University of Liège in Belgium, are far more down-to-Earth in their thinking, suggesting on the baton's discovery that they were used to weave something other than spells.

Now the two researchers have presented a proof-of-concept demonstration supporting their hypothesis.

In 2015, Conard, Rots, and a team of fellow researchers uncovered 13 pieces of worked mammoth ivory from Hohle Fels Cave in the Ach Valley – a 40,000-year-old site of occupation already famed for the discovery of what is regarded as the oldest representation of a human figure.

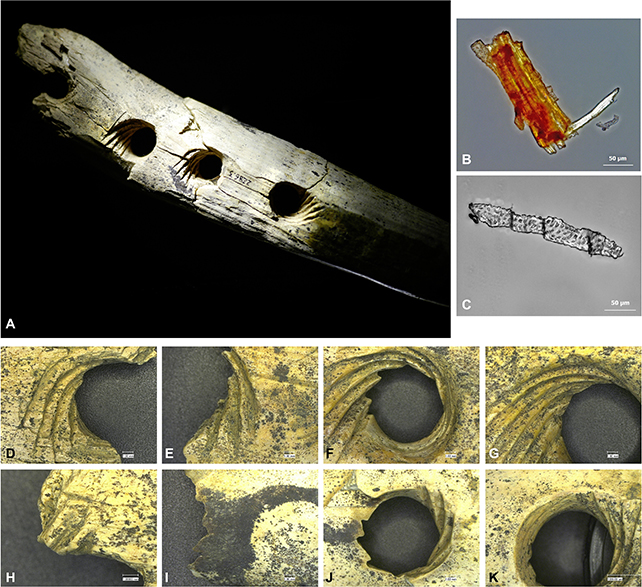

The ivory pieces fit together perfectly to form an object 20.4 centimeters (about 8 inches) in length, with four holes just wide enough to slip a pencil through. The worked ivory baton has no apparent purpose, at least not at first glance.

Yet thanks to its exquisite state of preserved grooves, coupled with plant fibers sifted from the surrounding soil, Conard and Rots were confident it was a tool for making one of the Stone Age's most precious resources – rope.

"This tool answers the question of how rope was made in the Paleolithic, a question that has puzzled scientists for decades," Rots said in 2016.

While items of stone, antler, and ivory can persist across the millennia, less durable materials like plant fiber are lost to time.

Yet rope, string, and thread would have been vital products in the Paleolithic, used to bind and secure everything from packaging to weapons to food to clothing. It's unthinkable that some kind of technology for making such material with ease wouldn't have existed.

To further demonstrate the artifact, along with a second less well-preserved 'perforated baton' (or Lochstab in German) found downstream from the site at Geißenklösterle Cave, were intended to make cordage, Conard and Rots reproduced a Lochstab of their own and put it to the test.

It was clear from the start the baton wouldn't be practical or necessary for making thinner ropes and threads. Yet using the holes as a guide, thicker cords consisting of two to four strands could be twisted quickly and efficiently.

The researchers tested various materials, including sinew from deer, hemp, flax, and nettles, finding cattail, linden, and willow fibers produced the best results.

With four to five participants holding the Lochstab replica and feeding the strands, the researchers were able to weave 5 meters of quality cattail rope that was both robust and flexible in just 10 minutes.

As with any replication, the experiment cannot prove beyond doubt that the artifacts served the same purpose, or were used in necessarily the same way. Just because an ancient artifact can be imaginatively used in a fashion doesn't mean it was, after all.

Similar objects may also have subtly different uses, perhaps for holding shafts while projectile points are secured, or straightening lengths of wood.

Coupled with microscopic analysis of the Hohle Fels Lochstab's grooves and plant fibers at the site, the puzzle of how high-quality ropes were produced thousands of years ago just might have its solution.

This research was published in Science Advances.