Galaxies that formed within the first few billion years after the Big Bang should have lived long, healthy lives. After all, they were born with rich supplies of cold hydrogen gas, exactly the fuel needed to continue star formation.

But new observations have revealed "quenched" galaxies that have shut off star formation. And astronomers have no idea why.

An international team of astronomers studied a group of six early galaxies with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Hubble Space Telescope. The results of the research were published recently in Nature.

Those galaxies were targeted because they were known to be "quenched", with little to no star formation.

Previously, astronomers believed that something intervened to stop star formation in those otherwise rich galaxies.

"The most massive galaxies in the Universe lived fast and furious, creating their stars in a remarkably short amount of time. Gas, the fuel of star formation, should be plentiful at these early times in the Universe," said Kate Whitaker, lead author on the study, and assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

"We originally believed that these quenched galaxies hit the brakes just a few billion years after the Big Bang. In our new research, we've concluded that early galaxies didn't actually put the brakes on, but rather, they were running on empty."

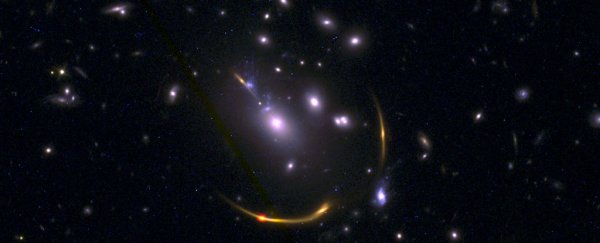

Usually, these kinds of galaxies are so distant that they're impossible to resolve, but the team behind the survey (called REQUIEM, for REsolving QUIEscent Magnified galaxies) used a trick: They used gravitational lensing around nearby galaxies to amplify the images of the target galaxies.

"If a galaxy isn't making many new stars it gets very faint very fast so it is difficult or impossible to observe them in detail with any individual telescope. REQUIEM solves this by studying galaxies that are gravitationally lensed, meaning their light gets stretched and magnified as it bends and warps around other galaxies much closer to the Milky Way," said Justin Spilker, a co-author on the new study, and a NASA Hubble postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin.

"In this way, gravitational lensing, combined with the resolving power and sensitivity of Hubble and ALMA, acts as a natural telescope and makes these dying galaxies appear bigger and brighter than they are in reality, allowing us to see what's going on and what isn't."

The team found that, contrary to expectations, there was no sudden drop in the ability for the galaxies to turn cold gas into stars. Rather, the stars were lacking the cold gas altogether.

"We don't yet understand why this happens, but possible explanations could be that either the primary gas supply fueling the galaxy is cut off, or perhaps a supermassive black hole is injecting energy that keeps the gas in the galaxy hot," said Christina Williams, an astronomer at the University of Arizona and co-author on the research.

"Essentially, this means that the galaxies are unable to refill the fuel tank, and thus, unable to restart the engine on star production."

But what is removing the cold gas from the galaxies? Astronomers are stumped and will have to continue their observations to find clues to this great galactic mystery.

"We still have so much to learn about why the most massive galaxies formed so early in the Universe and why they shut down their star formation when so much cold gas was readily available to them," said Whitaker.

"The mere fact that these massive beasts of the cosmos formed 100 billion stars within about a billion years and then suddenly shut down their star formation is a mystery we would all love to solve, and REQUIEM has provided the first clue."

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.