Until yesterday, Earth was the only tectonically active planet we knew of in our Solar System - a unique trait that's been linked to our planet's ability to host life.

But NASA has now found evidence that tiny planet Mercury has similar geological activity beneath its surface, including shifting pieces of crust and developing fault lines.

The evidence came from images captured by the MESSENGER spacecraft, which swooped in close to Mercury's surface during its last 18 months in orbit around the planet.

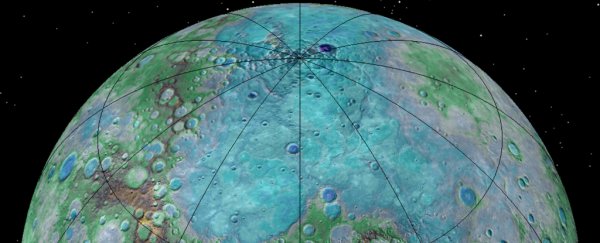

The photos showed previously undetected fault scarps - cliff-like landforms that resemble steps - on the smallest planet in our Solar System, and these scarps are small enough that scientists think they must be geologically young.

That suggests that Mercury is still contracting, and Earth is no longer the only tectonically active planet in the Solar System.

"The young age of the small scarps means that Mercury joins Earth as a tectonically active planet, with new faults likely forming today as Mercury's interior continues to cool and the planet contracts," said lead researcher Tom Watters, Smithsonian senior scientist at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

You can see those scarps below:

The bad news is that, despite its tectonic activity, Mercury remains pretty uninhabitable to life as we know it.

With only an 88 Earth-day orbit around the Sun, pretty much no atmosphere, and temperature fluctuations ranging from –173 degrees Celsius (–280 degrees Fahrenheit) at night to a scorching 427 degrees Celsius (800 degrees Fahrenheit) during the day, Mercury isn't exactly an ideal spot for life to evolve.

But the good news in all of this is that by better understanding this tectonic activity on Mercury, we're going to gain better insight into where it occurs, and how to spot it - potentially on worlds far beyond our Solar System.

And aside from Mercury and Earth, signs of tectonic activity have also been detected on Jupiter's water-laden moon Europa.

Europa's tectonic activity hasn't been confirmed, but as far as we can tell, Europa seems to be a much better candidate for hosting life than Mercury is. That's because it's believed Europa's tidal lock with Jupiter keeps its subsurface oceans warm enough to stay liquid.

(But being a moon, that still makes Mercury the first planet in our Solar System other than Earth to have suspected tectonic activity.)

The team will now continue to investigate Mercury's global magnetic field and surface activity to try to figure out more of what's occurring on the planet - there's also been evidence that the planet also experiences quakes, just like Earth does.

"This is why we explore," said NASA planetary science director Jim Green. "For years, scientists believed that Mercury's tectonic activity was in the distant past. It's exciting to consider that this small planet - not much larger than Earth's moon - is active even today."

The findings have been published in Nature Geoscience.