More than 100,000 babies born in the US every year start life in such close proximity to fracking sites that it could significantly damage their health, new research suggests.

Fracking – aka hydraulic fracturing – has long been criticised for its negative effects on the environment, but a new study analysing more than 1 million births provides what scientists say is the most damning evidence yet that fracking is bad for human beings.

"This study provides the strongest large-scale evidence of a link between the pollution that stems from hydraulic fracturing activities and our health, specifically the health of babies," economist and energy policy researcher Michael Greenstone from the University of Chicago told the Los Angeles Times.

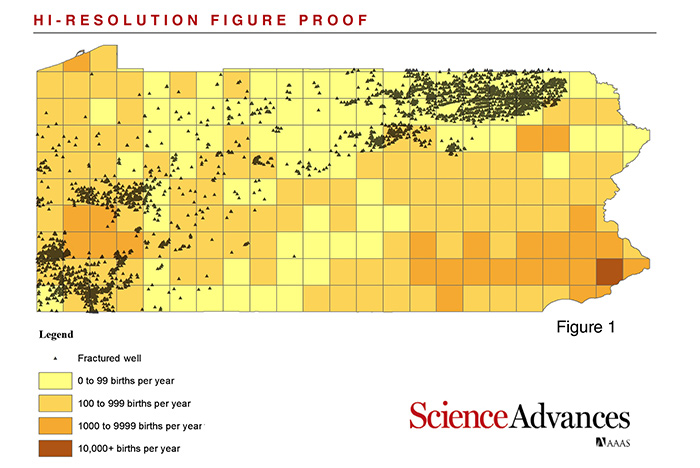

Greenstone and fellow researchers analysed records of more than 1.1 million births across Pennsylvania from 2004 to 2013, looking to see what differences if any were evident between babies born close to fracking sites compared to babies born further away.

(Janet M. Currie/Science Advances)

(Janet M. Currie/Science Advances)

What they found was that babies born within 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) of fracking sites start to show greater risk of being born at a low birth weight, which in turn increases their likelihood of things like infant mortality, ADHD, asthma, and lower educational and earning outcomes.

"Given the growing evidence that pollution affects babies in utero, it should not be surprising that fracking, which is a heavy industrial activity, has negative effects on infants," says economist and wellbeing researcher Janet M. Currie from Princeton University.

Outside of that 3 kilometre radius, no localised health effects were evident from fracking, but for babies born inside the zone, the danger seems to heighten the closer you get to drilling sites, as exposure to industrial pollutants increases.

Babies born within 1 kilometre (0.6 miles) of a fracking site were 25 percent more likely to be born underweight than babies outside the 3 kilometre radius. Infants who started life within 1 to 3 kilometres of the sites were also affected by their proximity, but less significantly.

Of course, just because these babies are born with lower body weight doesn't necessarily mean they'll develop any particular negative health outcomes later in life – but the fact that their in utero exposure to fracking is this evident is concerning, scientists say.

"Birth weight is a proxy: it gives us an insight into what's going on in gestation, and we worry a lot when we see changes like this," neonatologist Rebecca Simmons from the University of Pennsylvania, who wasn't involved with the study, told the Los Angeles Times.

"We know that babies born at low birth weight have a much, much higher risk of diseases such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity."

Due to the observational nature of the study, it's unclear for now what exact kinds of fracking-related pollutants or byproducts are doing the damage.

"While we know pollution from hydraulic fracturing impacts our health, we do not yet know where that pollution is coming from – from the air or water, from chemicals onsite, or an increase in traffic," one of the team, UCLA's Katherine Meckel, explains in a press release.

Determining the specific chemical culprits will fall to future research – as will further studies that could potentially track these infants as they grow up, which might tell us more about how their early exposure to fracking could be impacting them later in life.

For now, all we know for sure is that a lot of babies could be affected.

The researchers say of the 4 million or so babies born in the US each year, around 29,000 start life within 1 kilometre of a fracking site, while another 95,500 are born less than 3 kilometres from one.

There's a lot more research to do, but for some scientists, the takeaway is already clear.

"[W]e're beginning to see a pattern," healthcare researcher Madelon L. Finkel from Weill Cornell Medical College, who has done early research on this, explained to the Los Angeles Times.

"[Living near these sites does elevate risk compared to living further away."

The findings are reported in Science Advances.