An ancient sculpture carved by Paleolithic humans some 30,000 years ago is evidence that our ancestors were a restless bunch who roamed far and wide, new research has revealed.

Scientists have peered closely at the famous Venus of Willendorf and determined that the stone from which it is carved likely originated from Northern Italy, hundreds of kilometers from where it was eventually discovered in Austria in 1908.

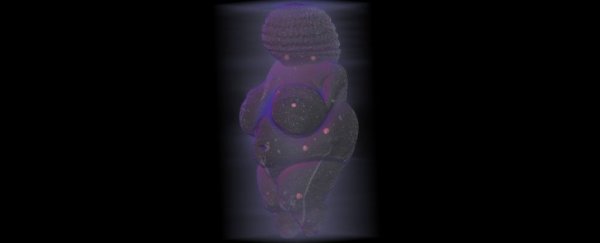

Venus of Willendorf is instantly recognizable. The enigmatic figurine, just 11 centimeters (4.3 inches) long, is striking. It has no feet or face, but exaggerated physical characteristics anthropologists typically associate with female fertility: exaggerated breasts, genitalia, and legs. In addition, the figurine sports an elaborate headdress or hairstyle.

The exact purpose of the carving is unknown; perhaps the artist just really liked big butts and cannot lie; but that's not the only mystery.

Other similar sculptures associated with the Gravettian culture from which Venus emerged tend to be carved from ivory or bone. Venus of Willendorf is carved from oolite, a type of sedimentary limestone made up of spherical grains called ooids. It's also stained red using ocher.

Previously, this sculpture had only been studied from the outside. In the new research, scientists led by anthropologist Gerhard Weber of the University of Vienna in Austria used micro-CT scanning to see what's inside the sculpture, down to a resolution of 11.5 micrometers.

The first thing they found is that the stone's internal structure is not uniform, but contains different layers of sediment, with different densities and grain sizes.

Images from micro-CT scanning that show the inclusions. (Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna)

Images from micro-CT scanning that show the inclusions. (Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna)

In addition, it contains inclusions – small pieces of shell, and larger iron grains called limonites. This meant the researchers could try to match the rock with oolite samples from the surrounding regions to narrow down where the rock might have come from.

A tiny shell remnant dating back to the Jurassic allowed them to rule out younger deposits. The next step was to conduct comparisons.

The researchers collected samples of rock from a swath of Europe stretching from France to Ukraine, some 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles) across, and compared the grain sizes to the Venus of Willendorf oolite. Fascinatingly, they found that there was nothing remotely similar within a 200-kilometer radius of Willendorf.

In fact, the closest match – so close that the rock is virtually indistinguishable – was from Lake Garda in northern Italy. That meant that Venus of Willendorf had to have traveled from south to north of the Alps, a route that would have been roughly 730 kilometers long if traveling around, rather than over, the mountainous region.

"People in the Gravettian – the tool culture of the time – looked for and inhabited favorable locations," Weber explains. "When the climate or the prey situation changed, they moved on, preferably along rivers."

Another potential match for the rock was also identified, but the researchers think it less likely – Ukraine, some 1,600 kilometers from Willendorf. Nevertheless, it can't be entirely ruled out.

Cavities in the Venus of Willendorf. (Kern, A. & Antl-Weiser, W. Venus. Editon-Lammerhuber, 2008)

Cavities in the Venus of Willendorf. (Kern, A. & Antl-Weiser, W. Venus. Editon-Lammerhuber, 2008)

However, while the exact provenance of the oolite cannot be definitively determined, studying the internal structure of the sculpture did yield other new information.

The researchers discovered that Venus' stone is porous because the cores of the ooids have dissolved over time. They also discovered that the limonites are likely the source of mysterious, hemispherical cavities found in the sculpture's surface, one of which constitutes the figure's belly button.

"The hard limonites probably broke out when the creator of the Venus was carving it," Weber says. "In the case of the Venus navel, [they] then apparently made it a virtue out of necessity."

Of course, the finding reveals how precious the sculpture must have been to whoever carried it on such a long and arduous journey.

"The exact time when the Venus was created or its material collected and transported is unknown," the researchers write in their paper.

"However, independent of the location of origin, we can state with certainty that its individual owners kept and protected it en route."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.