Alzheimer's is a deadly, devastating disease, as frightening for people faced with the condition as it is challenging for scientists studying it. Now, scientists have made a small but promising discovery about a well-known culprit behind Alzheimer's disease, a protein called tau.

The new research suggests that sticky tau tangles gobble up small molecules of nucleic acid and other proteins that brain cells simply cannot live without.

This could help explain certain cellular defects seen in the brain tissue of individuals who have died from the disease; it also points to a common disease pathway linking several neurodegenerative diseases, including less common forms of dementia.

"Understanding how tau leads to neurodegeneration is the crux of not just understanding Alzheimer's disease but also multiple other neurological diseases," said biochemist Roy Parker from the University of Colorado Boulder.

"If we can understand what it does and how it goes bad in disease, we can develop new therapies for conditions that now are largely untreatable."

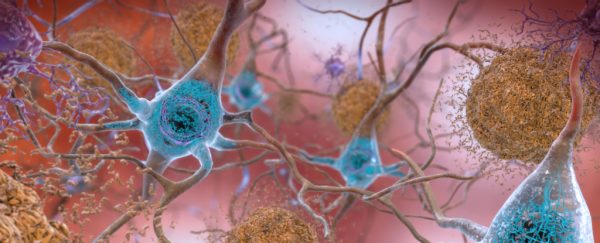

Besides tau, there are also amyloid proteins to consider. These proteins form clumps called plaques, whereas tau twists into so-called neurofibrillary tangles. Both are thought to clog up and kill brain cells, but exactly how is still a question many are asking.

Amyloid plaques and tau tangles are two of the hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease, a neurological condition marked by memory loss and slow cognitive decline, which Alois Alzheimer first described in 1906.

Since amyloid and tau's involvement in neurodegeneration processes were first discovered decades ago, the two proteins have been the focal point of much dementia research.

However, the 'amyloid hypothesis' – which casts amyloid as the main culprit in Alzheimer's disease – has come under much scrutiny in recent years, as most clinical trials of drugs targeting amyloid aggregates have ended in disappointment.

Evidence has also emerged against amyloid plaques as the primary cause of disease. As a result, some researchers have suggested that perhaps we need to focus on tau since amyloids may not be as involved as we once thought.

It's not just Alzheimer's disease where tau appears to be toxic. The protein has also been tied up in other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's disease and the concussion-related syndrome known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Together, these conditions are collectively known as 'tauopathies'.

In the new study, which featured an animal model of Alzheimer's disease and lab-grown cells, the researchers showed that tau tangles contain conglomerates of RNA, single-stranded molecules of ribonucleic acid – that should be helping to make proteins in the nucleus, not bundled up outside the cell.

Tau tangles were also seen interfering with nuclear speckles, granular clusters that help to process freshly transcribed RNA before it leaves the nucleus en route to becoming a working protein. Part of this process involves 'splicing' together useful sections of RNA and cutting out what's not needed.

What the researchers observed is that part of the cell's splicing machinery appeared to be sucked out of nuclear speckles and into tau aggregates, and they think that this could be a deadly disruption for brain cells.

"The tau aggregates appear to be sequestering splicing-related RNA and proteins, disrupting their normal function and impairing the cell's ability to make proteins," said study author and medical researcher Evan Lester.

The results also go some way to explaining common disease features observed in affected individuals, after Lester and his co-authors noted similar changes in post-mortem brain tissue samples from people who had died with Alzheimer's disease or other neurological disorders, such as frontotemporal dementia.

"These results raise the possibility that tau aggregation per se is responsible for some of the splicing changes seen in disease tissue," they write in their paper.

By exposing tau's role in sequestering splicing proteins, the study also presents news targets for drug discovery – though, as we've seen with amyloid, that's a long road to travel with no guarantees of success.

"The idea would be to intervene in the abnormal functions while preserving the normal functions of tau," Lester said.

"A big problem in the field is that no one really knows what tau does in healthy people, and it likely has important functions when not in tangles," he added.

So even with this study providing new insights, it's early days yet.

Other research has suggested tau might have a protective role in aging, upending other hypotheses entirely. And we've seen plenty of claims before that 'we may finally know what causes Alzheimer's disease, which unfortunately are never quite the whole story.

For now, what we're looking at is another significant discovery – but many questions remain.

The study was published in Neuron.