When Italian explorer Christopher Columbus and his Spanish troops returned to Europe from the Americas in the late 15th century, they notoriously brought back the deadly pathogen responsible for syphilis. Or so the story goes.

The truth might not be quite so clear cut. Past studies of medieval bones and teeth have hinted that the bacterium Treponema pallidum, or closely related strains, could have been circulating around Europe long before Columbus returned from his first voyage in 1493.

Far from excusing Columbus for seeding a scourge that swept through Europe (nor for the diseases Spanish fleets carried to the Americas, killing scores of Indigenous people), a more complex picture of T. pallidum's prevalence in earlier centuries is emerging with newfound evidence.

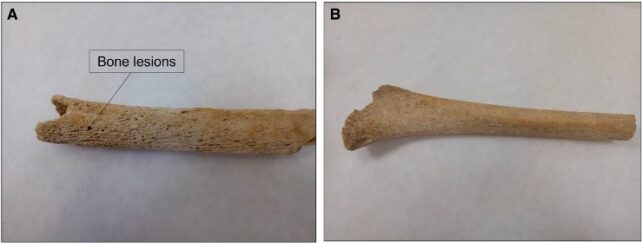

A new study from a team of paleomicrobiologists adds weight to that counter-hypothesis, finding signs of a T. pallidum infection in a thigh bone from 7th or 8th century France. Aside from recovering fragmented DNA of a possible ancestral strain of T. pallidum, the researchers also detected antibodies specific to T. pallidum in the diseased femur.

"These data break a century-old dogma in medical microbiology," Hamadou Oumarou Hama, an infectious disease researcher at Aix-Marseille University in France, and colleagues write in their published paper.

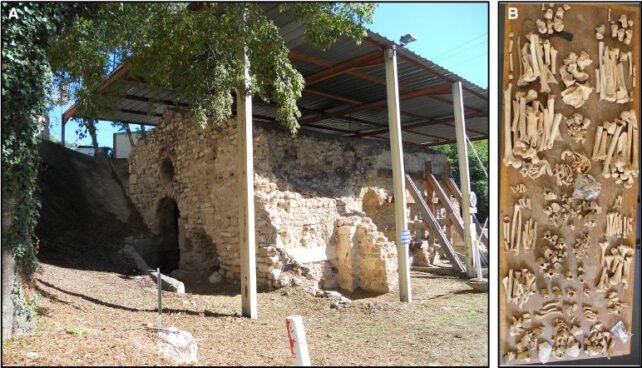

Archeological excavations in 1987 uncovered the diseased femur among a heap of other bones buried at Chapelle Saint-Vincent in Roquevaire, France, although its significance was not realized until years later.

Examining the pockmarked bone, Hama and colleagues went to great lengths to ensure it and the extracted samples weren't contaminated by other sources of DNA, working in a lab that had never processed T. pallidum DNA before.

The extracted DNA resembled a small portion of the T. pallidum reference genome, and antibodies were found in a pulverized sample of the diseased femur, but neither were detected in another unmarred bone from the same burial site used as a control.

If accurate, the findings push the presence of T. pallidum infections in Europe back by eight centuries, the researchers say.

"To the best of my knowledge," Aix-Marseille University microbiologist and co-author Michel Drancourt told journalist Maryn McKenna for Wired, "this is the first, proven, strong piece of evidence that the Treponema of syphilis were circulating in the European population before Columbus."

Not everyone is convinced, though. According to McKenna, historians cannot find evidence of syphilis outbreaks before those that tore through Europe in the 1490s.

Plus, different subspecies of the spiral-shaped Treponema bacteria cause different diseases. A subspecies called T. pallidum pertenue can cause a distinct disease called yaws, while abother subspecies, called endemicum, can cause what's known as bejel. Both are skin infections, though neither are transferred by sexual contact like syphilis is.

While Hama and colleagues might have detected a Treponema infection of some kind, they can't definitively conclude it caused syphilis; it might have been a subspecies that caused yaws, for example.

The damaged DNA from the 1,400-year-old bone covered just 2.4 percent of the pallidum subspecies genome, but was near-identical to those sections, leaving room for debate.

The suggestion, from some medical experts – and even Hama and colleagues – is that mounting evidence points to pertenue or endemicum likely being in Europe before Columbus returned, perhaps with an unfamiliar, more infectious strain, pallidum, then coming from the Americas.

In time more evidence may well come to light, adding more detail to this topsy-turvy story of syphilis' origins and rounding out the history of this still-stigmatized disease.

The study has been published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases.