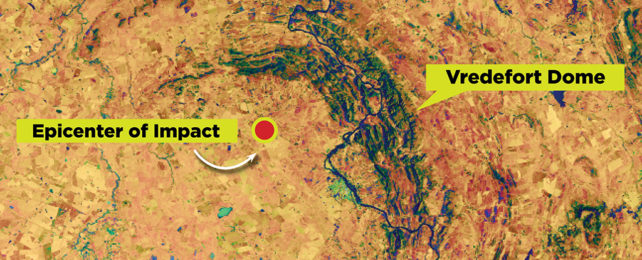

The Vredefort crater in South Africa is the largest of its kind on Earth, estimated to stretch as far as 300 kilometers (more than 180 miles) from rim to rim. Walking non-stop, it would take a good two-and-a-half days to make it from one side to the other.

The scars left by an asteroid collision some two billion years ago have long since been all but scoured away by the elements, leaving room for speculation over its true scale and the forces that created it. Now new research based on what's thought to be a more accurate simulation of the impact event suggests that the object that made the crater was larger than previously believed.

Earlier estimates put the asteroid at 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) in diameter, traveling at a velocity of 15 kilometers per second.

This latest analysis suggests the object responsible for the crater was closer to 20 to 25 kilometer across, traveling at a velocity of 15 to 20 kilometers per second in the moments before impact.

"Understanding the largest impact structure that we have on Earth is critical," says astrophysicist Natalie Allen, from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

"Having access to the information provided by a structure like the Vredefort crater is a great opportunity to test our model and our understanding of the geologic evidence so we can better understand impacts on Earth and beyond."

The number crunching was done by the widely used Simplified Arbitrary Lagrangian Eulerian (iSALE) simulation model, resulting in a scenario supporting earlier research that pushes the estimated size of the Vredefort crater to a higher range – way beyond the size that a 15 kilometer-wide asteroid would create.

Of course two billion years is a lot of time for a landscape to wear away, so estimating the original size of the crater with accuracy isn't straightforward. Its location is now covered in farmland, with the crater's central dome the only structure still visible today.

If the new modeling is correct, the asteroid that hit two billion years ago would have been bigger than the one that created the Chicxulub crater and killed off the dinosaurs some 66 million years back in time. Most estimates put that crater at around 180 kilometers (112 miles) across.

"Unlike the Chicxulub impact, the Vredefort impact did not leave a record of mass extinction or forest fires, given that there were only single-cell lifeforms and no trees existed two billion years ago," says planetary scientist Miki Nakajima, from the University of Rochester in New York State.

"However, the impact would have affected the global climate potentially more extensively than the Chicxulub impact did."

Dust and aerosols thrown up by the impact would have blocked out the Sun and cooled Earth's surface, the researchers say. This may have continued for days or even decades, possibly leading to a greenhouse effect that significantly raised the temperature of our planet.

The simulation work done here also gives researchers a better insight into how land masses might have evolved over time. Material from the Vredefort impact has been spotted as far away as what is modern-day Russia, but the researchers think this location would have been much closer to the impact crater two billion years ago.

All of which leads to a better understanding of how our planet has evolved over billions of years, through huge geological and ecological change, and in spite of several hefty impacts from asteroid collisions.

"It is incredibly difficult to constrain the location of land masses long ago," says Allen. "The current best simulations have mapped back about a billion years, and uncertainties grow larger the further back you go."

"Clarifying evidence such as this ejecta layer mapping may allow researchers to test their models and help complete the view into the past."

The research has been published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.