Astronomers developed a set of equations that can precisely describe the reflections of the Universe that appear in the warped light around a black hole.

The proximity of each reflection is dependent on the angle of observation with respect to the black hole, and the rate of the black hole's spin, according to a mathematical solution worked out by physics student Albert Sneppen of the Niels Bohr Institute in Denmark in July 2021.

This was really cool, absolutely, but it wasn't just really cool. It also potentially gave us a new tool for probing the gravitational environment around these extreme objects.

"There is something fantastically beautiful in now understanding why the images repeat themselves in such an elegant way," Sneppen said in a 2021 statement.

"On top of that, it provides new opportunities to test our understanding of gravity and black holes."

If there's one thing that black holes are famous for, it's their extreme gravity. Specifically that beyond a certain radius, the fastest achievable velocity in the Universe, that of light in a vacuum, is insufficient to achieve escape velocity.

That point of no return is the event horizon – defined by what's called the Schwarszchild radius – and it's the reason why we say that not even light can escape from a black hole's gravity.

Just outside the black hole's event horizon, however, the environment is also seriously wack. The gravitational field is so powerful that the curvature of space-time is almost circular.

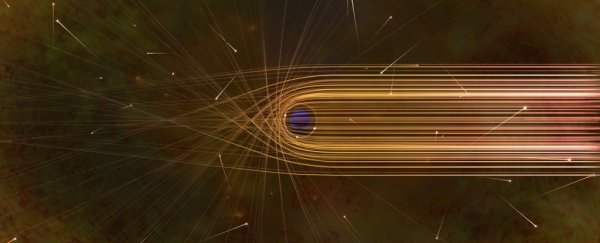

Any photons entering this space will, naturally, have to follow this curvature. This means that, from our perspective, the path of the light appears to be warped and bent.

At the very inner edge of this space, just outside the event horizon, we can see what is called a photon ring, where photons travel in orbit around the black hole multiple times before either falling towards the black hole or escaping into space.

This means that the light from distant objects behind the black hole can be magnified, distorted, and 'reflected' several times. We refer to this as a gravitational lens; the effect can also be seen in other contexts and is a useful tool for studying the Universe.

So we've known about the effect for some time, and scientists had figured out that the closer you look toward the black hole, the more reflections you see of distant objects.

To get from one image to the next image, you needed to look about 500 times closer to the black hole's optical edge, or the exponential function of two pi (e2π), but why this was the case was difficult to mathematically describe.

Sneppen's approach was to reformulate the light trajectory and quantify its linear stability, using second order differential equations. He found not only did his solution mathematically describe why the images repeat at distances of e2π, but that it could work for a rotating black hole – and that repeat distance is dependent on spin.

"It turns out that when it rotates really fast, you no longer have to get closer to the black hole by a factor of 500, but significantly less," Sneppen said. "In fact, each image is now only 50, or five, or even down to just two times closer to the edge of the black hole."

In practice, this is going to be difficult to observe, at least any time soon – just look at the intense amount of work that went into the unresolved imaging of the ring of light around supermassive black hole Pōwehi (M87*).

Theoretically, however, there should be infinite rings of light around a black hole. Since we have imaged the shadow of a supermassive black hole once, it's hopefully only a matter of time before we're able to obtain better images, and there are already plans for imaging a photon ring.

One day, the infinite images close to a black hole could be a tool for studying not just the physics of black hole space-time, but the objects behind them – repeated in infinite reflections in orbital perpetuity.

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.

An earlier version of the article was first published in July 2021.