Astronomers have known for some time that the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxies will collide on some future date. The best guess for that rendezvous has been about 3.75 billion years from now.

But now a new study based on Data Release 2 from the ESA's Gaia mission is bringing some clarity to this future collision.

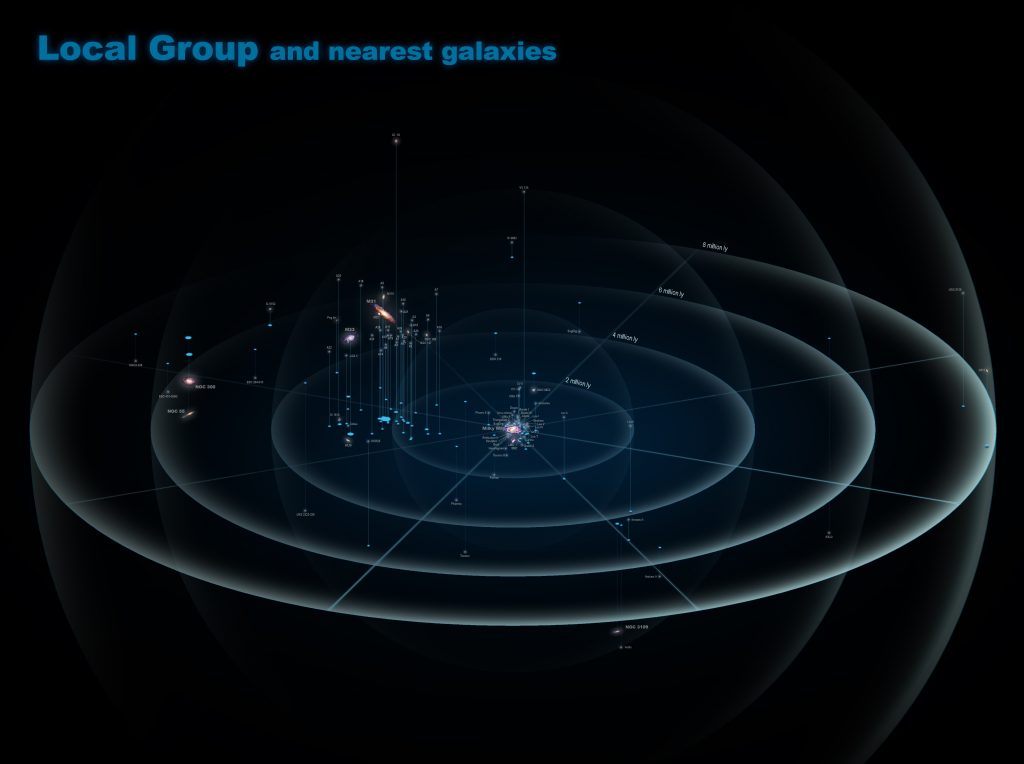

There's more to the overall collision picture than just the Milky Way and Andromeda (M31). The two galaxies are part of a group of galaxies called the Local Group, and the Local Group has a third large member, the Triangulum Galaxy (M33).

Though the Local Group contains other galaxies, it's the aforementioned three that make up the majority of the mass.

Of the three, the Andromeda is the most massive, the Milky Way is the second most massive, and the Triangulum is the third.

Local Group of galaxies, including Andromeda and Milky Way. (Wikipedia Commons/Antonio Ciccolella)

Local Group of galaxies, including Andromeda and Milky Way. (Wikipedia Commons/Antonio Ciccolella)

The Local Group is made up of more than 54 different galaxies, though most of them are dwarf galaxies, gravitationally attached to the big three. The gravitational center of the Group is somewhere between the Milky Way and Andromeda.

Though a collision has been predicted for some time now, there's still lots of uncertainty. The Hubble Space Telescope and other ground-based 'scopes like the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) have provided the observational evidence for this collision.

With that data, astronomers have been able to learn a little about how the orbits of the Andromeda and the Triangulum have changed over time.

The Andromeda and the Triangulum are both spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, and they are somewhere between 2.5 and 3 million light years away from us.

They're also close enough to potentially be interacting gravitationally, which muddies the collision predictions.

This is where the ESA's Gaia mission comes in.

"We needed to explore the galaxies' motions in 3D to uncover how they have grown and evolved, and what creates and influences their features and behaviour," says lead author Roeland van der Marel of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, USA.

"We were able to do this using the second package of high-quality data released by Gaia."

The Gaia mission is making a 3D map of our Milky Way galaxy, and it's also doing the same for parts of the Local Group.

While 'scopes like Hubble give us sharp views of the other members of the Local Group, they don't give us the accurate measurements of positions and motions of individual stars. That's Gaia's mission.

"We combed through the Gaia data to identify thousands of individual stars in both galaxies, and studied how these stars moved within their galactic homes," adds co-author Mark Fardal, also of STScI.

"While Gaia primarily aims to study the Milky Way, it's powerful enough to spot especially massive and bright stars within nearby star-forming regions – even in galaxies beyond our own."

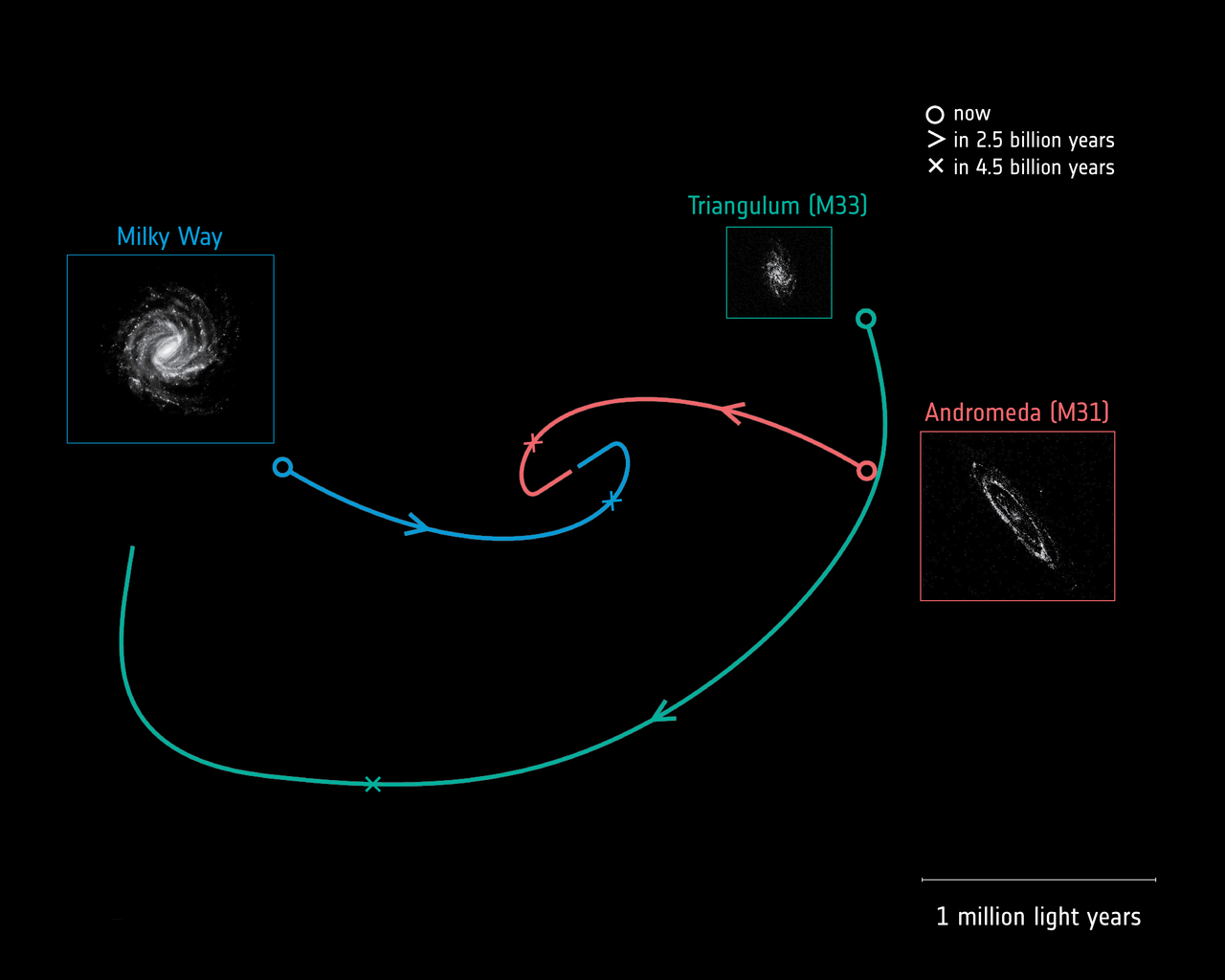

In the past, when astronomers used the Hubble and other observatories to study the motions of the Local Group's three largest members, they found two possibilities.

Either the Triangulum galaxy is on an incredibly long six-billion-year orbit around Andromeda but has already fallen into it in the past, or it is currently on its very first in-fall.

Each scenario reflects a different orbital path, and thus a different formation history and future for each galaxy.

But now Gaia has given astronomers much more data to work with. Not only does it reveal how the galaxies are moving through space, it shows their spin rate.

This spin-rate data has long been coveted, ever since astronomers began studying galaxy formation and evolution a hundred years ago, and Gaia has finally delivered.

"It took an observatory as advanced as Gaia to finally do so," says Roeland. "For the first time, we've measured how M31 and M33 rotate on the sky. Astronomers used to see galaxies as clustered worlds that couldn't possibly be separate 'islands', but we now know otherwise."

"It has taken 100 years and Gaia to finally measure the true, tiny, rotation rate of our nearest large galactic neighbour, M31. This will help us to understand more about the nature of galaxies."

The researchers behind the study combined existing data with the new data from Gaia Release 2 to create a more accurate picture of how Andromeda and the Triangulum are moving through space.

They were able to project this into the past and into the future for billions of years.

"The velocities we found show that M33 cannot be on a long orbit around M31," says co-author Ekta Patel of the University of Arizona, USA. "Our models unanimously imply that M33 must be on its first infall into M31."

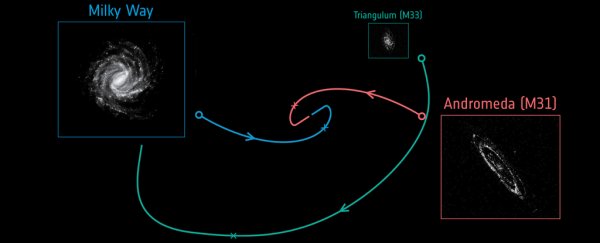

Galaxy trajectories. (E. Patel/G. Besla/University of Arizona/R. van der Marel/STScI)

Galaxy trajectories. (E. Patel/G. Besla/University of Arizona/R. van der Marel/STScI)

The study also revealed more of what's in store for the Milky Way and Andromeda. Rather than a collision (which is more accurately called a tidal interaction since no stars or planets were ever likely to collide), there's going to be more of a glancing blow.

And rather than taking place in about 3.75 billion years, it'll be in about 4.5 billion years. Phew!

The new paper, and the new data from Gaia, also shed some light on how galaxies like Andromeda and Triangulum form and evolve.

"This finding is crucial to our understanding of how galaxies evolve and interact," says Timo Prusti, ESA Gaia Project Scientist. "We see unusual features in both M31 and M33, such as warped streams and tails of gas and stars. If the galaxies haven't come together before, these can't have been created by the forces felt during a merger."

"Perhaps they formed via interactions with other galaxies, or by gas dynamics within the galaxies themselves."

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.