Being curious is a quintessential part of being human, driving us to learn and adapt to new environments. For the first time, scientists have pinpointed the spot in the brain where curiosity emerges.

The discovery was made by researchers from Columbia University in the US, who used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans to measure oxygen levels in different parts of the brain, indicating how busy each region is at any one time.

Knowing where curiosity originates could help us understand more about how human beings tick, and potentially lead to therapies for conditions where curiosity is lacking, such as chronic depression.

"This is really the first time we can link the subjective feeling of curiosity about information to the way your brain represents that information," says neuroscientist Jacqueline Gottlieb.

During their experiments, the researchers gave 32 participants special images called texforms, where familiar objects and animals – such as hats or frogs – are distorted to varying degrees. The volunteers were asked to rate their confidence and curiosity about identifying the subject of each texform.

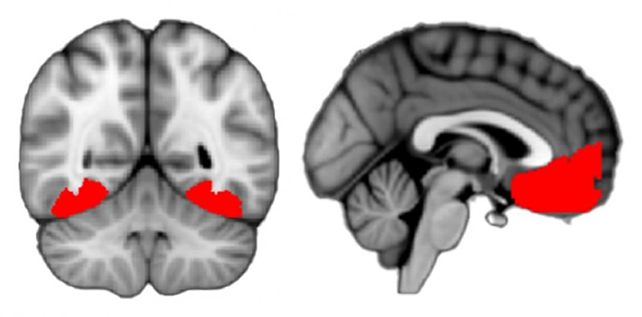

These ratings were cross-referenced with the fMRI scans, and notable activity was spotted in three regions: the the occipitotemporal cortex (linked to vision and object recognition), the ventromedial prefrontal cortex or vmPFC (which manages perceptions of value and confidence), and the anterior cingulate cortex (used for information gathering).

The vmPFC appears to act as a sort of neurological bridge between levels of certainty recorded by the occipitotemporal cortex, and subjective feelings of curiosity – almost like a trigger telling us when to be curious. The less confident the volunteers were about the image subject, the more curious they were about it.

"These results illuminate how perceptual input is transformed by successive neural representations to ultimately evoke a feeling of curiosity," write the researchers in their published paper.

As well as potential therapeutic value, the researchers also want to investigate how these findings might apply to other types of curiosity beyond image identification: being curious about trivia and facts, for example, or social curiosity about the activities of others.

Part of what makes the research so fascinating is that curiosity is a fundamental part of being human, key to our survival as a species. Without it, we're not as good at learning and absorbing new information, and there's evidence it drives biodiversity too.

"Curiosity has deep biological origins," says Gottlieb.

"What distinguishes human curiosity is that it drives us to explore much more broadly than other animals, and often just because we want to find things out, not because we are seeking a material reward or survival benefit."

The research has been published in the Journal of Neuroscience.