The time has come. We're going to smash a spacecraft into an asteroid.

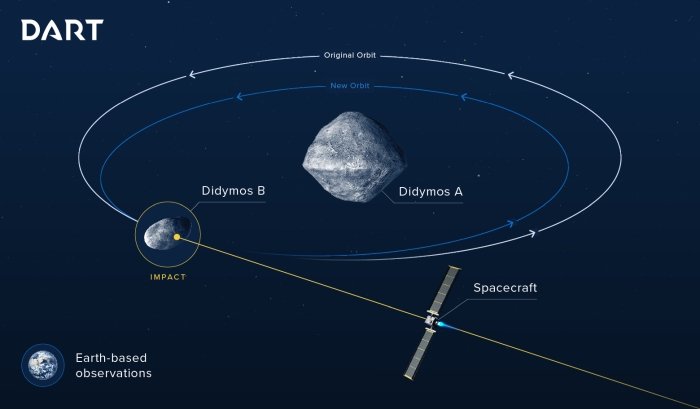

The asteroid is Didymos B, the smaller of the two objects in the Didymos binary asteroid system. The spacecraft is NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). The reason: to test whether a spacecraft impact can deflect an asteroid's trajectory, as a means to protect Earth from rogue space rocks.

The joint asteroid impact and deflection assessment (AIDA) project by the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA was announced in 2015, but recent surprise findings from subsequent asteroid missions may have implications for the test.

For example, when JAXA's Hayabusa2 bombed asteroid Ryugu in April of this year, it made a much bigger crater than expected. In addition, the material on the asteroid's surface behaves a lot like sand; that could influence the effectiveness of kinetic impact deflection.

"The impact with Hayabusa2 showed that there was no cohesion on the surface and the regolith behaved like pure sand. Gravity was dominating the process, rather than the intrinsic strength of the material from which the asteroid is made," explained planetary scientist Patrick Michel of CNRS.

"If gravity is also dominant at Didymos B, even though it is much smaller, we could end up with a much bigger crater than our models and lab-based experiments to date have shown. Ultimately, very little is known about the behaviour of these small bodies during impacts and this could have big consequences for planetary defence."

Following an AIDA workshop last week in Rome, scientists have met at the EPS-DPS Joint Meeting 2019 in Geneva to discuss the project further.

"Today, we're the first humans in history to have the technology to potentially deflect an asteroid from impacting the Earth," astronomer Ian Carnelli of the ESA told Technology Review.

"The key question that remains to be answered is, are the technologies and models that we have good enough to actually work? Before you drive a car, you need to have an insurance policy. Well, AIDA is the insurance policy for planet Earth."

The Didymos system is the perfect testbed, too. It's a near-Earth object - so, not too far away - that isn't on a collision course with Earth, meaning our tests are unlikely to backfire.

"DART's target, Didymos, is an ideal candidate for humankind's first planetary defence experiment," said planetary scientist Nancy Chabot of Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

"It is not on a path to collide with Earth, and therefore poses no current threat to the planet. However, its binary nature enables DART to trial and evaluate the effects of a kinetic impactor."

In this asteroid binay, the larger object, Didymos A, is around 780 metres across; the smaller, Didymos B, is 160 metres, and is sometimes called "Didymoon". It orbits the larger asteroid every 11.92 hours.

When DART rams into Didymos B at a speed of 23,760 kilometres per hour (14,760 miles per hour), it will only change the asteroid's speed very slightly - by just a centimetre per second or so.

More like Didyboom! (NASA/Johns Hopkins APL)

More like Didyboom! (NASA/Johns Hopkins APL)

In a single asteroid, we might not be able to detect this at all; but in the Didymos system, the impact is expected to slightly change the orbital period. Rather than 11.92 hours, Didymos B may take a few minutes more to go around Didymos B.

That doesn't sound like much, but if we can intercept an Earth-bound asteroid early enough, that small velocity change could make all the difference.

DART is on schedule to launch in July 2021, for an impact in September 2022. A small cubesat called LICIAcube will detach from the spacecraft just prior to take photos of the impact to beam back to Earth. And Earth-based telescopes will subsequently observe Didymos to see if the transit times change based on regular dips in the system's light curve.

The second part of the mission is the ESA's Hera. This is a small observation spacecraft that will launch in 2023, and arrive to take observations of Didymos B in 2027. Since we can't really see the asteroid system clearly from Earth, Hera will be able to tell us all the finer details - such as, for instance, if the DART impact makes Didymos B wobble longitudinally.

Hera has passed its system requirements review, and is now proceeding into the development stage.

"Planetary defence is really a worldwide endeavour," Carnelli told Technology Review.

"Besides just the technology and the science, AIDA is also a really good experiment in terms of collaboration between scientists and agencies around the world. It's the sort of thing that would be needed were an asteroid on a collision course for Earth."